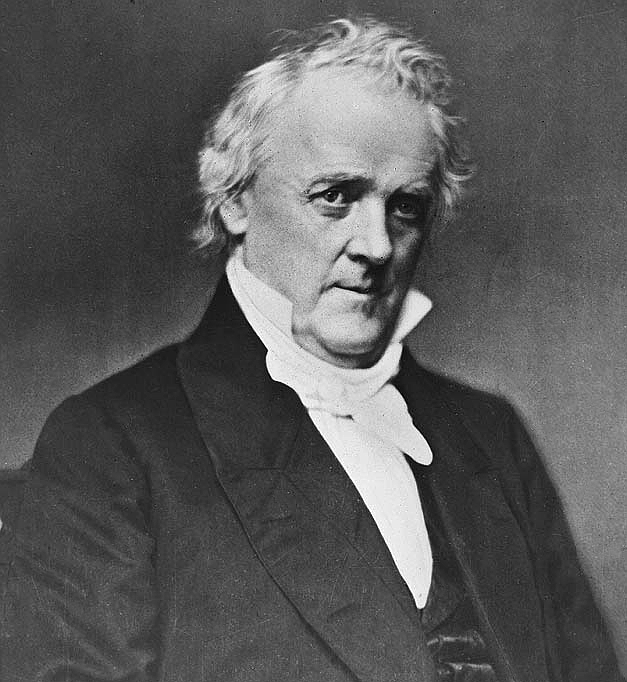

Our 15th U.S. president, James Buchanan, is the only president to have been a confirmed bachelor his entire life. He was engaged once, in 1819, to a girl from a wealthy family, but rumors of affairs with both other women and men and suggestions he was marrying her only for her money, as well as his lengthy trips away from her, caused her to break off the engagement. James wrote to her father to ask for permission to attend the funeral when she died shortly after breaking up with him, but this permission was denied.

Buchanan wrote once in his later years that he might marry a woman who could accept his lack of passion and romantic inclinations. He also lived with a man as roommates for many years, and their friendship was a noted close one, with even contemporaries commenting on it. His roommate, William Rufus King, was described by contemporaries as Buchanan’s “better half” and “Aunt Fancy” (which was a 19th century way of describing an effeminate man). Modern historians suspect Buchanan may have been asexual, purposefully celibate after losing his fiancée, or homosexual. As his and King’s nieces and nephews seem to have destroyed most correspondence between the two, we may never know the truth of the matter.

Ultimately, Buchanan’s romantic life, or lack thereof, had no impact on his presidency or historical legacy. And, like all U.S. presidents before him, he had his First Lady. During Buchanan’s presidency, this role was filled by his niece, Harriet Lane.

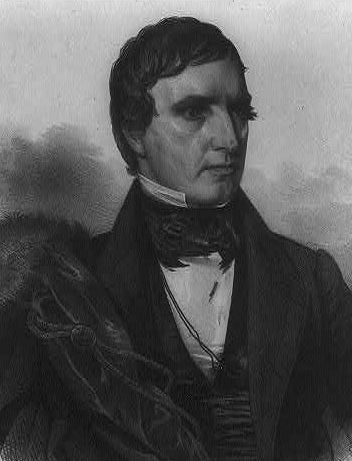

Harriet Rebecca Lane Johnston was born May 9, 1830, in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, the youngest child of Elliot Tole Lane and Jane Ann Buchanan Lane. Harriet lost both parents by the time she was eleven… her father when she was nine, and her mother two years later. Upon becoming an orphan, Harriet and one of her elder sisters requested their favorite uncle, their mother’s brother, the future U.S. president James Buchanan, be appointed their legal guardian. James obliged his nieces’ request.

James enrolled Harriet and her sister at a couple of different exclusive boarding schools in Virginia and Washington, D.C. He also introduced them both into the high-class circles of fashionable and influential people in these areas, as he had promised them when he became their guardian.

James was already involved in a successful political career when he took in Harriet and her sister, and in 1854, Harriet went with him on a diplomatic trip to the United Kingdom. Here, she met Queen Victoria in person, where the Queen called her “dear Miss Lane,” and gave her the official rank of Ambassador’s Wife, though Harriet was unmarried at the time. Harriet had many suitors in Great Britain and was acclaimed there as a great beauty, being of medium height with famed golden blonde hair.

When Buchanan became President in 1857, Harriet went with him to the White House, with American newspapers welcoming the arrival of their “Democratic Queen.” She quickly became popular as a White House hostess and admired by regular American women for her style and fashion. When Harriet lowered the neckline on her Inaugural Ball gown by 2 ½ inches, other American women followed suit, and it became a trend. In fact, most of Harriet’s hair and clothing styles were watched closely by Washington insiders and national newspapers, and women and girls all over the country copied her. Harriet was possibly America’s first real famous fashion trendsetter.

Harriet’s popularity as First Lady went beyond just her hair and clothes, as well. She threw well-received parties, was a gracious hostess and was generally admired by all who came into contact with her in Washington, D.C. This fame made its way into national newspapers, and women across the country began naming their daughters after her, and a popular song called “Listen to the Mockingbird” was written about her. Harriet Lane seemed to inspire anyone who heard about her, even if they didn’t meet her in person. She was a bit like a 19th century Kardashian, famous for being famous (only with more substance and personality behind her).

This substance can be viewed through the lens of history in the social causes Harriet used her position as First Lady to promote. A favorite of hers was improving the living conditions of Native Americans on reservations. She loved art and culture and invited both popular and up-and-coming artists, writers, and musicians to the White House. Historians today compare her popularity among the regular people of the nation to that of Jacqueline Kennedy and call her the first of the truly modern First Ladies. The presidential yacht was even named after her, as were several other ships of the time, one of which is still in service today.

As Buchanan’s presidency progressed, tensions between pro and anti-slavery proponents became intense. Harriet began planning her White House parties with great care, especially the ones where people had to sit next to each other. She was adept at making seating charts that gave diplomats their due deference while keeping foes apart. However, near the end of Buchanan’s presidency, the task became an impossible one, as seven states had seceded from the Union by the time Buchanan left office. Harriet’s grace and tact never wavered, though, even in the face of these political tensions in her home.

After Buchanan left office in 1861, Harriet moved with him to his spacious county manor home near Lancaster, Pennsylvania. While she was in England, the attorney general to the Prime Minister proposed marriage to her, among many other suitors, and Queen Victoria was in favor of it, as she wished to keep Harriet in England. Harriet, however, found her suitors to be pleasant, but, as she described them, “troublesome.” Buchanan advised her to not rush into marriage. Harriet took this advice seriously, and carefully considered a number of them before eventually committing to one when she was over 35 years old.

Her husband was Henry Elliot Johnston, a banker from Baltimore. She had two sons with him. However, 18 years after marrying Johnston, Harriet found herself all alone, as, in that time, James Buchanan, Henry Johnston, and both of her sons died.

When Harriet wrote her will in 1895, the prosperity of the 1890s made her estate quite valuable. She directed that a substantial portion of it be dedicated to building a school for the training of choirboys on the grounds of the Washington National Cathedral. She wished this school to be called the Lane-Johnston Building, so, as she said, the names of she and her late husband could be preserved in memory of their sons. The building exists today as the St. Albans School.

Harriet also left $400,000 to build the Harriet Lane Home for Invalid Children as a memorial to her sons, both of whom had died in childhood. When it opened in 1912, it was the first children’s home in the United States with a medical school attached to it. Groundbreaking research was done there, innovative treatments were developed, and it continues to do so today as the Harriet Lane Outpatient Clinic, which has branches all around the world. The manual used by pediatric house officers is still called the Harriet Lane Handbook.

Her birthplace was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972. Harriet herself died in 1903 and is buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland. She wanted her name and her husband to live on in memory of her sons. As far as her own name goes, Harriet more than succeeded.