Family stories have a way of becoming family legends, and one of the most common you’ll hear in genealogical circles is this: “Our ancestor came through Ellis Island, and the clerks changed the family name because they couldn’t spell it.”

It’s dramatic, almost cinematic. Imagine the scene—ships crowding New York Harbor, weary travelers clutching suitcases, and an impatient official scribbling down a “new” surname that forever altered the family’s story.

But here’s the reality: Ellis Island clerks did not change names.

The truth is both less theatrical and more interesting, because it says something important about how myths form, how families adapt, and where the real records are hiding.

How Ellis Island Really Worked

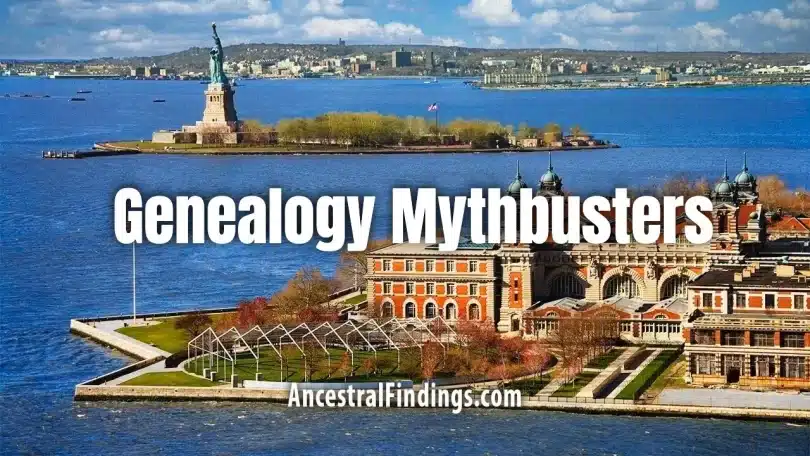

Ellis Island opened in 1892 as the main federal immigration station in New York Harbor and processed over 12 million immigrants before closing in 1954. The job of the clerks was not to create new names but to verify information already collected.

Before boarding a ship in Europe, immigrants gave their names, ages, and other details to shipping agents, who created the ship’s passenger manifest. By the time passengers reached Ellis Island, those manifests were the official record. Clerks at Ellis Island simply checked the new arrivals against these lists. If anything didn’t match, it raised suspicion—not opportunity for creative spelling.

So if clerks weren’t changing names, where did the idea come from?

Why the Myth Spread

There are a few reasons this story became so sticky in American families:

- Immigrants changed their names later. Once settled in the U.S., many people simplified or Anglicized their names to fit in, find jobs, or avoid discrimination. “Schmidt” became “Smith,” “Giovanni” became “John.” These changes could look sudden in the records.

- Language differences caused confusion. Transliteration—the act of rendering one alphabet into another—often changed spellings. A surname written in Cyrillic or Polish orthography rarely matched neatly with English spelling.

- Clerical variations were normal. Even before Ellis Island, clerks wrote names phonetically. If your great-grandfather said his name with a thick accent, the spelling might shift from one record to the next without anyone “changing” it on purpose.

- The myth is a neat explanation. Families trying to explain why Grandpa was born “Ivanov” but died “Evans” found the Ellis Island story a tidy scapegoat.

Where Names Actually Changed

If you’re researching your family tree, don’t waste time blaming Ellis Island. Instead, look in the following places:

- Naturalization records: Immigrants sometimes filed for a formal name change when becoming citizens. Courts recorded both the old and new names.

- Employment records: Employers sometimes “simplified” names for paperwork—or employees changed them to avoid bias.

- School and church records: Teachers and clergy often wrote names as they understood them, leading to gradual shifts.

- Everyday use: The most common explanation—families simply started using a new version of their name in daily life.

Real-Life Examples

To make this concrete, here are a few patterns you might see:

- A Hungarian man named “János Kovács” appears on his ship manifest exactly as written. Ten years later in Detroit, he’s “John Kovach” on the census. By the time his children are adults, the family name is just “Koch.” None of this happened at Ellis Island—it happened in neighborhoods, workplaces, and schools.

- A German family named “Schwarzkopf” arrived in New York with their name intact. In the 1920s, facing anti-German sentiment after World War I, they quietly began using “Black” instead. Again, the decision was personal, not official.

Research Tips for Tracing Name Changes

So what should you do when names shift across records? Here are practical steps:

- Start with the passenger manifest. Many are digitized on sites like Ancestry, FamilySearch, and EllisIsland.org. These documents show the name as it was recorded at departure.

- Track naturalization papers. These can reveal both old and new identities. Some even list aliases.

- Use city directories. These often capture when someone began using a new spelling or shortened version.

- Look at census records side by side. You’ll sometimes see a family’s surname morph over two or three decades.

- Search variant spellings. Think phonetically. “Kwiatkowski” might appear as “Kwitkoski,” “Kwitkowsky,” or even “Quitkoski.”

The Deeper Story

The Ellis Island myth persists because it captures a real feeling: the tension between old-world heritage and new-world assimilation. While the paperwork didn’t force these changes, life in America often did.

Families chose to reshape their identities—sometimes reluctantly, sometimes strategically. They shortened names for business success, switched spellings to match their neighbors, or translated surnames into English. These were acts of survival, adaptation, and sometimes pride.

So instead of picturing a harried clerk scribbling out your ancestor’s past, imagine the more complex truth: your family making decisions, large and small, about how to balance tradition with opportunity.

Ellis Island didn’t change names—people did. And in that decision lies a much more powerful story than the myth suggests. The choices your ancestors made about their names reflect resilience, creativity, and adaptation in the face of a new life.

When you dig into the records, don’t just chase the “real” spelling. Follow the journey of the name itself. Each version tells a chapter of the immigrant experience.