Marriage records are one of the three core types of vital records every family historian should learn to use. Birth, marriage, and death records often work together like a three-legged stool. If you are missing one leg, the whole picture feels shaky. A marriage record can connect a woman’s maiden name to her married name, link parents to children, confirm relationships you only guessed at, and point you toward a new place to search.

Even better, a marriage record often answers questions you did not know to ask. It may tell you where the bride and groom lived at the time, how old they were, whether either had been married before, who performed the ceremony, who witnessed it, and sometimes the names of parents or even grandparents. In some areas, the record will also name the bondsman, surety, or person who permitted the marriage, which can be a close relative and a valuable clue.

Marriage records also help you avoid classic traps. Many people share the same name, especially in the same county. A marriage record can separate two men named John Smith by showing different ages, residences, or spouses. It can also help you place the right children with the right couple, because the marriage date provides a timeline that can be compared with census records and birth records.

Below is a practical guide to finding marriage records, including what to search for, where to look, and what to do when the official record is gone.

Start With What You Already Know

Before you start requesting records, pull together a small “starter file” for the couple.

Write down:

- Full names, including the bride’s maiden name if you know it

- An estimated marriage year

- Where they lived in the first census, where they appear together

- Names and birth years of the first two children

- The county or town where the first child was born, if known

This does two things. First, it helps you guess where the marriage most likely happened. Second, it provides enough context to confirm that you found the right couple when you discover a record.

A quick timeline can also help you narrow the window. If their first child was born in 1886, the marriage might be from 1883 to 1886, but it could be earlier. Some couples had children several years after marrying, and some older couples married after being widowed.

Understand What “Marriage Record” Can Mean

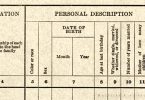

People say “marriage record” as if it were one single document. In practice, it can be several different things.

Depending on the place and time, you might find:

- Marriage license, the permission to marry

- Marriage application, often with ages, birthplaces, parents, and prior marriages

- Marriage bond, common in many southern states and earlier periods

- Marriage banns, a church announcement of intent to marry

- Marriage register, a county book entry

- Marriage return or certificate, showing that the ceremony happened

- Church marriage record, sometimes more detailed than the county record

- Newspaper announcement, engagement, wedding notice, or anniversary piece

Do not stop searching just because you did not find a “certificate.” You might locate a bond, a license, and a return instead. Together, they can be even better than a single-page certificate.

Ask Family, and Ask Wider Than You Think

Relatives are often the fastest route to marriage information, especially for 1900s marriages when privacy rules can make government copies hard to obtain. Family collections might hold original certificates, church keepsakes, wedding invitations, photos, or Bible entries. These are not only useful, but they can also point you straight to the county or church where the official record is stored.

Also, do not limit yourself to relatives you have met in person. Many marriage records and family papers survive because they were kept by one branch of the family rather than another. A distant cousin might have the one document your direct line lost.

This happens more often than you would think. Courthouses burn. Floods destroy files. Clerks misfile things. Families move and throw away “old papers.” Yet a decorative church certificate, a Bible page, or a small envelope of keepsakes survives in a drawer somewhere. When you connect with a cousin online and share what you have, you increase the odds that someone will return the favor with something you never expected.

Practical tip: When you write a cousin, be specific. Instead of asking, “Do you have anything?” ask, “Do you have a marriage certificate, wedding photo, Bible record, or obituary for John and Mary who married about 1870 and lived in Burke County?”

Go Local: County and Town Records Often Beat State Offices

State vital records offices are helpful, but they are not the whole story. Many states only began statewide registration in the late 1800s or early 1900s. Even after that, coverage can be spotty. County and town offices often kept marriage books long before states centralized records.

If you suspect the marriage is older, or if the state office says it cannot find it, shift your search to:

- County courthouse or county clerk

- Town clerk (especially in New England and parts of the Northeast)

- Parish or church archives

- Local archives or county historical society

Counties and towns often keep records back to their earliest days. That is why a record from the early 1800s might be sitting in a county marriage book even if the state has nothing that early.

Two quick strategies help here:

- Identify the county where the couple lived in the first census after marriage. That county is a strong candidate for the marriage location.

- Identify the bride’s family location. Many marriages happened near the bride’s parents.

If you can visit in person, do it. Suppose you cannot write a clear letter or email. Include full names, estimated year range, and a request for a copy, and the citation details from the marriage book. Ask what the fee is and how they want to be paid.

Use Census Clues That People Overlook

Census records do not replace a marriage record, but they can point you to one.

Examples:

- 1900 and 1910 censuses often include years married (and sometimes the number of marriages for the woman)

- A couple appearing together for the first time in a new county can hint that they married shortly before moving

- A household with older children whose surname differs from the head of household can suggest a prior marriage for the wife

If a census says “married 30 years” in 1900, that suggests a marriage about 1870. It is not proof of an exact date, but it narrows your search window and can guide you to the correct marriage entry in a county register.

Search Church Records, Not Just Civil Records

In many periods and places, churches recorded marriages long before government offices did, and sometimes they recorded extra details such as:

- Both sets of parents

- The home parish of each person

- Witnesses, who were often siblings or close relatives

- Notes about permissions or prior marriages

If you know the family’s religion, look for baptism records for children. Baptisms can name the church. Once you know the church, you can search for marriage entries in the same records.

If you do not know the church, look at cemetery records and obituaries. These often name the church where the funeral was held, which can lead you to a long standing family congregation.

Old Newspapers Can Be Pure Gold

Newspapers are one of the best substitutes when you cannot find the official record, and they can also add details the official record never would.

You might find:

- Wedding announcements with parents’ names

- A description of the ceremony and location

- Names of attendants and guests, often relatives

- Engagement notices

- Anniversary celebrations with a recap of the original marriage date and place

If you can find the newspaper online, search using multiple approaches:

- The couple’s full names and partial names

- The groom’s last name with the bride’s first name

- The word “married” with the surname

- Variations in spelling

If the newspaper is not online, check local libraries, state archives, and historical societies. Many have microfilm. Some will do a lookup for a small fee if you provide a date range.

Try Court Records, Guardianship Files, and “Consent” Clues

When a bride or groom was underage, consent was often required. That consent might appear in the marriage record, or it might be filed separately in court records. If you suspect an underage marriage, look for:

- Consent statements signed by a parent or guardian

- Guardianship records if one parent had died

- Probate records that name minors and guardians

- Court minutes that mention permission to marry

These can be especially useful because they directly connect the young person to a parent or guardian, which helps confirm the right family.

Watch for Name Problems and Second Marriages

Marriage research is where name problems show up in full force.

Common issues:

- The bride’s last name is spelled wrong or written differently

- Widowed women marrying under a previous married name, not their maiden name

- Men with the same name in the same county are marrying different women

- A couple marrying more than once due to religion, location, or legal reasons

If you cannot find the marriage, try searching for the bride under a prior married surname. Also, check for earlier marriages for each spouse. A “mystery” middle-aged marriage might be a second marriage after a spouse died.

When the Courthouse Burned or the Record Is Gone

Sometimes the record really is missing. That does not mean you are stuck.

Build a proof case using multiple sources:

- Church marriage entry or church certificate

- Newspaper marriage notice

- Census years married

- Land records showing husband and wife together soon after the marriage

- Probate records naming a spouse

- Children’s birth or baptism records naming both parents

- Obituaries naming a spouse and marriage date

- Cemetery records or family Bible records

A strong family history conclusion is often built from several pieces that agree with each other. One document is nice. A stack of independent documents that all point to the same marriage is even better.

Keep Good Notes and Cite Everything

Marriage research gets messy fast, especially when you are dealing with repeated names. Keep a research log.

Track:

- Where you searched

- What date range do you search?

- What spelling variations have you tried?

- What you did and did not find

Also record complete source citations for anything you do find, including book page numbers, certificate numbers, and the office that provided the copy. In the future, you will be grateful.

Marriage Records Are More Than Dates

A marriage record is not just a line on a tree. It is a doorway. It can lead you to parents, siblings, old hometowns, church communities, and even migration patterns. It can also bring a couple into focus as real people, making choices in a real place, surrounded by real witnesses.

Finding them can be straightforward. It can also turn into a hunt through courthouses, church ledgers, microfilm, and cousin connections. Either way, it is worth the effort because marriage records often provide the link that holds an entire generation together.