Lady Jane Grey is known to the world today as England’s “Nine Days Queen.” She was never crowned, and her reign was the briefest in English history. However, this outstanding young woman’s story is not limited to this brief and tragic reign as Queen of England. Jane was much more than that. In fact, she was an inspiration to an entire religious movement after she crossed to the other side and is widely viewed as an early Protestant martyr. She was also one of the most intelligent and highly educated women of her day. This is her story.

Jane was born in October of 1537 (estimated by most historians) to Lord Henry Grey and Lady Frances Brandon. Henry was a direct descendant of Thomas Grey, the eldest son of Queen Elizabeth Woodville (wife of King Edward IV) by her first husband, Sir John Grey. Frances was the daughter of Mary Tudor, former Queen of France and younger sister to King Henry VIII. Frances’s father, Charles Brandon, was Henry VIII’s childhood best friend. So, Jane was the granddaughter of a princess, great-granddaughter to a king (Henry VII), and great-niece to another king (Henry VIII).

In her childhood, she was fourth in the line of succession to the English throne according to the will of Henry VIII, which bypassed the children of his elder sister, Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scotland, for those of his younger sister, Mary. After Henry crossed over and his son Edward became king, the only people ahead of Jane in line to the throne were Henry’s daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, and Jane’s mother, Frances. It was an enviable place to be and an extremely privileged life for a young lady in those times. Yet, being that close to the throne was also a dangerous position to be in at times, usually for men but occasionally for women, as well, as Jane would discover. She would also learn that when one was that close to the throne, one couldn’t always even trust one’s own parents.

Jane grew up highly educated. She read classical books in the original Latin and Greek when she was still a child and was tutored by the same man who tutored her cousin, Princess Elizabeth (who later became Queen Elizabeth I). When she was ten years old, she was “fostered out” by Queen Dowager Katherine Parr and her new husband, Thomas Seymour. This was a common practice among noble families of the time, as it was thought that living with a different family would allow a child to learn all of the socially pleasing and courtly manners and skills they needed to know without being coddled by an overly affectionate family.

In this regard, Jane actually had it better at Katherine Parr’s house, where her cousin, Princess Elizabeth, was also being fostered after Henry VIII’s crossing to the other side. Jane’s parents were notoriously cruel to her (as evidenced by recollections of those who knew her and some of her own writings), whereas Katherine Parr was affectionate and kind. Unfortunately, Jane had to go live with her own parents again sooner than was planned after Katherine crossed over due to childbirth and Thomas Seymour was arrested for treason (for planning to kidnap King Edward VI, who was his nephew through his sister, the late Queen Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII).

Jane’s parents were ambitious for her, as well as for their other two daughters, Katherine and Mary, who were Jane’s younger sisters. As the eldest surviving child in the family, though, their highest ambitions were placed on Jane. This can perhaps explain, along with the different child-rearing methods of the time, why they were so hard on her.

After Thomas Seymour’s execution, and later, that of his brother Edward, who had been the young king’s regent, a new regent took over. His name was Thomas Dudley. Thomas had ambitions for his own large family of children. Being so close to the king, he wanted to make sure he kept the power this brought him. When the plans Jane’s parents had for her to marry her cousin, the King (who was the same age as her), fell through, Thomas soon had a solution that would benefit all of them.

By the time they were young teenagers, it was clear that King Edward and Jane would not wed, as Edward was showing signs of being ill with what was probably tuberculosis. Thomas hastily got Jane’s parents to agree to her marrying his youngest son, Guilford. Then, he warned the young king that his half-sister Mary would inherit his throne if he did not write his own will. Since Mary was a Catholic and Edward was a devoted Protestant, he did not want England to become a Catholic nation once more. At Thomas’s urging, and knowing he was probably going to cross over soon, King Edward VI made his own will, naming his cousin and fellow Protestant, Lady Jane Grey as his heir (bypassing her mother, Frances, at Frances’s request, since she was not likely to have more… particularly male… children).

Jane was now the heir to the throne on paper, though Parliament had not yet ratified Edward’s will when he crossed at age fifteen, which was required for the will to be legally binding. Instead, the Lords of the realm swore their fealty to Queen Jane and promised to ratify the will at the soonest convenience of Parliament.

Jane was duly informed she was Queen, which was a total shock to her and not something she wanted in the slightest. She protested that the crown was not hers by right but Mary’s. The Lords of the realm, her parents, her in-laws, and, finally, her young husband cajoled her until she relented and agreed that, if it was God’s will, she would be Queen.

As was the custom at the time, Jane was taken to the Tower of London to await her coronation. English monarchs at the time used the Tower as their official residence between the time of being proclaimed monarch and their coronation ceremony. She spent nine days there, signing documents, making proclamations, being named godmother to people’s babies, and deciding who among her supporters should go lead an army against Princess Mary, who was putting together an army of her own to take the crown.

Mary had an advantage over Jane in that she had the support of the common people of England, who viewed her as the rightful heir. With the public’s support, she soon had plenty of troops on her side to take the crown. Jane’s supporters quickly defected to Mary’s side, with her father-in-law being among the first and her own father the last. Jane, Guilford, Jane’s parents, and Guilford’s mother, were all left in the tower alone, except for the guards, who prevented them from leaving. Jane had naively hoped she could just happily give up the crown she never wanted and go home, but that is not how royal political games played in England in the mid-1500s.

Jane was a prisoner in the same Tower where she was supposed to be crowned Queen. Mary (now Queen Mary I, sometimes known to history as Bloody Mary for her persecution of Protestants during her five-year reign) allowed Jane’s parents and Guilford’s mother to leave, but Jane and Guilford were kept as prisoners in different parts of the Tower from each other.

As Jane was her cousin, and she had known her since she was born, as she and Jane’s mother were close with each other growing up (they were first cousins to each other), Mary was inclined to let Jane go after a time, once the commotion over Jane’s being given the crown had lessened. She knew Jane did not take the crown of her own doing, that she was forced into it by the adults around her. After all, Jane was only sixteen years old. Mary even had a face-to-face meeting with Jane about it and promised to let her go after Jane’s mandatory trial and probable sentence of execution for treason. Mary, as Queen, had the right to commute that sentence, and she intended to do it.

Sadly, Mary’s choice of husband, Prince Philip of Spain, proved controversial among the English nobles, who did not want Spain controlling England, as a husband must control his wife. Jane’s father, who had been easily pardoned and released months prior by Mary’s goodwill toward Jane’s mother, was one of the nobles who participated in Wyatt’s Rebellion, which was intended to force Mary to choose for herself a different husband. While Jane’s father was not doing this to put Jane on the throne once more, some people in the rebellion were heard shouting out in favor of Queen Jane.

Jane’s father was captured hiding in a hollowed-out tree trunk and sent to the tower. Though Mary knew Jane had done nothing wrong and was innocent in all of this, she also knew that as long as Jane lived, she would be a threat to her crown. This wasn’t because Jane wanted the crown but because others would seek to put her on it. Jane had written a letter to Mary that still exists, explaining her side of everything, saying her only sin was in allowing the crown to be placed upon her head. Presumably, she also told Mary this at their in-person meeting soon after Mary took the throne. Mary went back and forth with herself over the matter of what to do with Jane for quite a while. Eventually, though, she decided that in order to secure the safety of her crown, she had to have Jane executed.

Jane’s father was also sentenced to execution for his part in Wyatt’s Rebellion. Jane’s father-in-law had been executed months before for conspiring to put Jane on the throne in the first place. Jane’s husband Guilford, only eighteen years old, was also sentenced to be executed on charges of conspiring to put Jane on the throne, though he hadn’t actually done anything wrong, either. He was just too close to Jane to be allowed to go free.

Jane was given an opportunity to convert to Catholicism before she was executed. Mary cared about her cousin’s soul and believed only conversion would assure her admittance to heaven. Jane thought the same thing about Mary converting to Protestantism. Much to Jane’s annoyance, Mary delayed her execution by three days to send her own personal priest to Jane to convince her to convert. Jane refused but did come to like and respect the priest. She asked him to accompany her to the scaffold, which he did.

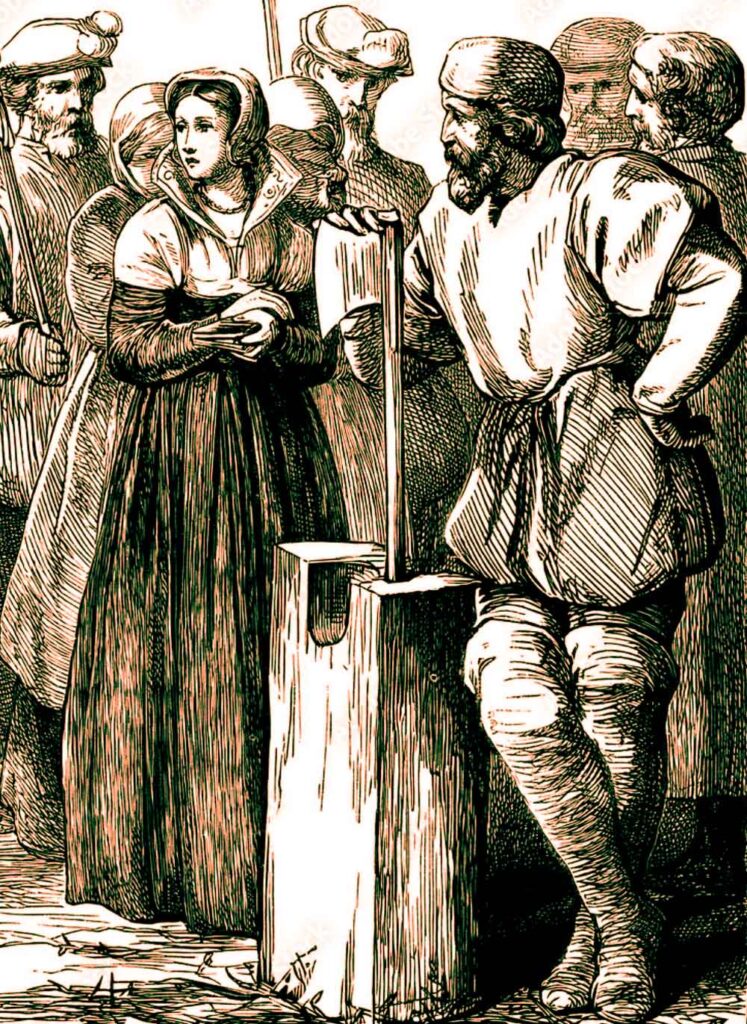

Jane was executed by beheading in February of 1554. She was sixteen years old. Guilford had been executed earlier that morning. While he had asked to see Jane in person one more time before they were dispatched to the other side, and Mary had granted permission for this, Jane refused, saying it would just cause them both too much pain and they would see each other in heaven, where they would be happier. She promised to watch him out of her window in the Tower as he went to the scaffold, which she did, giving him a wave as he went. When his bloody, headless body was brought back the same way shortly after, she cried out his name upon seeing this and broke down into tears.

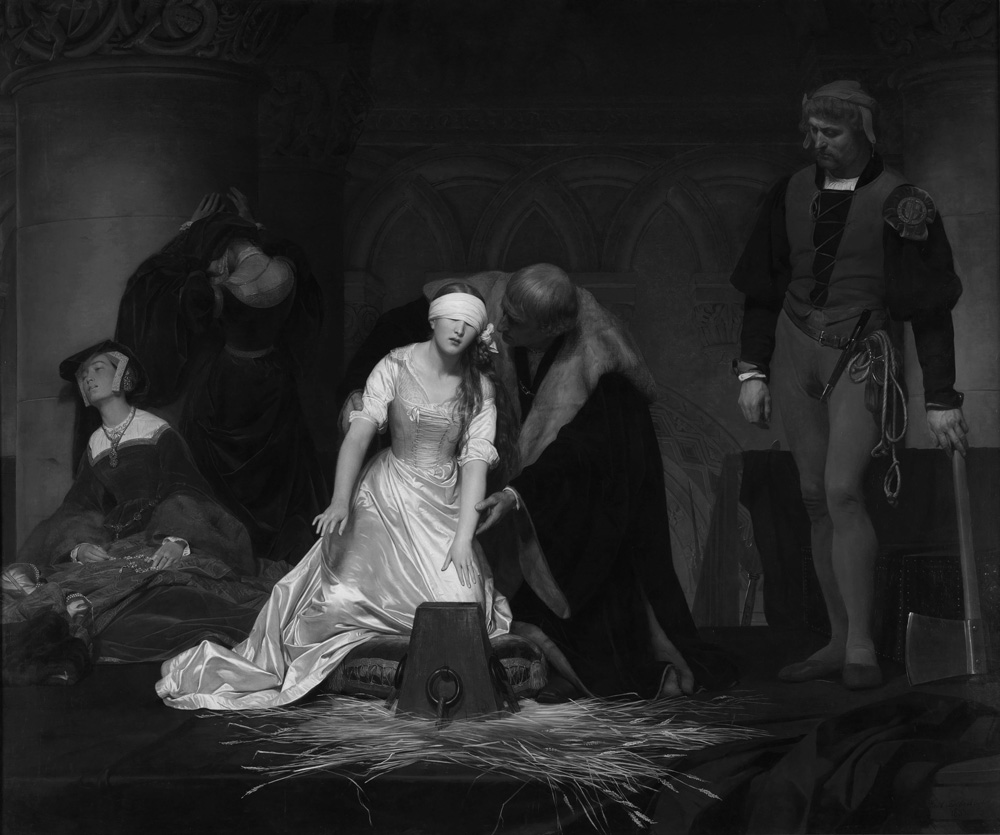

When she went to the scaffold about an hour later (a private one within the tower grounds, not the public one Guilford went to, due to her royal birth), she was composed. She gave a speech, asked the ax man if he would take off her head before she was ready (to which he said no), recoiled, and asked him not to touch her when he attempted to assist her in disrobing (it was customary to give the victim’s clothing to the executioner as part of his payment since it was often expensive, valuable clothing), insisted on blindfolding herself rather than letting her attendant ladies do it for her, gave the warden of the Tower her prayerbook (which still exists today, with inscriptions she made in it herself), and attempted to find the block on which to put her head.

She couldn’t find it with the blindfold on and briefly lost her composure, crying out that she couldn’t find it and didn’t know what to do. An unknown person in the small crowd who gathered to watch assisted her by guiding her hand to the block. She was beheaded in one stroke while praying for God to accept her soul.

Jane’s father was beheaded two weeks after his daughter. Jane’s mother had tried to get Mary to pardon him, but not her own daughter. After the executions, Mary welcomed her beloved cousin Frances and her two remaining children, the Ladies Katherine and Mary Grey, to court to be among her treasured and well-treated and provided-for-serving ladies, which were highly sought-after positions among the nobility.

Jane is buried alongside her father, father-in-law, and husband near the altar in the Chapel of St. Peter-ad-Vincula within the grounds of the Tower of London, near such other notable famous executed royalty as Anne Boleyn, Katherine Howard, Margaret de la Pole, George Boleyn, Jane Parker, Thomas and Edward Seymour, and others. Her final resting place can be visited today on a Yeoman Warder’s tour of the Tower of London. Her childhood home of Bradgate Manor with its surrounding park, though in ruins today, can also be visited, and picnicking is allowed in the park. Though Jane is not remembered by history today as much as some other English royalty, her story is nonetheless a remarkable one, and a testament to her strength of character and deep, unbending faith, even at such a young and tender age. She is well worth remembering and even celebrating. She is an inspiration to all.