The wife of 19th US President Rutherford B. Hayes, Lucy Ware Webb Hayes was born August 28, 1831, in Chillicothe, Ohio. She was to become a remarkable and pioneering First Lady in some ways. She was the first First Lady to have a college degree, she was a known teetotaler and proponent of abstinence, a passionate abolitionist, and a strong advocate for voting rights and equal pay for women. However, before she could become all of these things, she had to get there. This is her intriguing and eye-opening story. Lucy Hayes was a woman ahead of her time.

Lucy’s father, James Webb, was a doctor, and her mother, Maria Cook, was a homemaker. Her two older brothers also became doctors. The Webb family were against slavery, and quite outspoken about it. This was so much so that when Lucy’s father inherited between 15 and 20 slaves from his aunt in Lexington, Kentucky, he traveled there to free them. When he arrived, he found a cholera epidemic going around the slave community on his aunt’s farm, and as a doctor, he stayed to nurse them back to health. Unfortunately, James Webb eventually contracted cholera as well, and died, leaving Maria a widow with three children to raise.

Maria’s friends urged her to sell the slaves to earn money to keep her house and food on the table for her children. Maria refused, saying she would take in washing herself to earn money rather than sell a slave. She freed them all, just as her husband wished. These early experiences had a strong impact on young Lucy.

Lucy was only two years old when her father died. When she was 13, her mother moved the family to Delaware, Ohio, so her brothers could attend college there. They enrolled at Ohio Wesleyan University. The college did not accept women at the time, but it allowed Lucy to take classes at its college prep program.

After finishing her studies at Wesleyan, Lucy enrolled at Cincinnati Wesleyan Female College, bringing with her a report from the dean at Wesleyan in Delaware, Ohio that her conduct there had been exemplary. While a student at Cincinnati Wesleyan, Lucy enjoyed writing essays on religious and social issues, particularly women’s rights. It is not known whether she developed her beliefs in this area from her upbringing or while at college, but they were lifelong beliefs at least since sometime during her college years. In one essay she wrote in college, Lucy said,

“It is acknowledged by most persons that her (woman’s) mind is as strong as a man’s… Instead of being considered the slave of man, she is considered his equal in all things, and his superior in some.”

Lucy first met her future husband, Rutherford B. Hayes, while still at the college prep program at Wesleyan in Delaware, Ohio. She was 14, and he was 23 at the time. Rutherford’s mother hoped the two might connect, but he felt Lucy was still a bit too young for him to fall in love with her. The Hayes family did not forget about Lucy, however, and after her graduation from college in 1850, Rutherford’s sister, Fanny Hayes Platt, encouraged him to reconnect with her. Rutherford duly visited the now 19-year-old Lucy, and the two did fall in love as hoped this time.

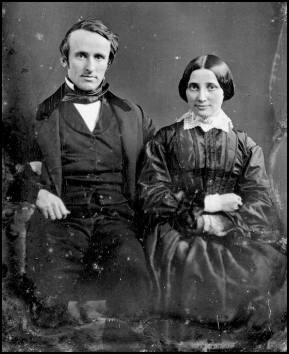

Rutherford & Lucy Hayes on their wedding day: December 30, 1852. (Wikipedia)

They were married at Lucy’s mother’s house on December 30, 1852. They spent their honeymoon at Fanny Platt’s house in Columbus, Ohio, where Rutherford, a lawyer, argued a case before the Ohio Supreme Court, while Fanny and Lucy became close friends. The two women attended lectures and concerts together, including several lectures by noted women who spoke for voting rights for females in America. Fanny Platt was passionate about these causes, and many historians now believe that if Fanny hadn’t died in childbirth four years later, she would have made Lucy into an even stronger supporter and advocate for the rights of women than she already was.

Lucy named the 6th of her eight children, and her only daughter, after her sister-in-law, Fanny Hayes Platt.

It was not only women’s rights that Lucy advocated for. She also argued strongly on behalf of the abolition of slavery. She even influenced Rutherford in this regard, as he originally felt abolition was too radical a change for this country and would never work. Lucy’s arguments convinced him otherwise, and he began working for abolitionist causes, including protecting runaway slaves from being returned to the south if they reached Ohio.

When the Civil War began, Lucy was enthusiastic about it, and her enthusiasm caused Rutherford to enlist as a major in the 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Lucy took her children and mother to visit him at camp often and even helped her brother, Dr. Joe Webb, tend to the ill and injured there. She came to camp so often, wherever it was at the time, always to help the soldiers as well as spend time with her husband, the members of Rutherford’s regiment began calling her “Mother Lucy.”

Rutherford spent time as a member of Congress and served three terms as governor of Ohio after the Civil War. Lucy often attended Congressional debates he participated in, wearing a checkered shawl so he could spot her in the gallery, and founded a home for the orphans of soldiers while she was First Lady of Ohio. Rutherford’s success as governor of Ohio brought him to national prominence, and he was nominated as the Republican candidate for US President in the election of 1876.

By the time Lucy became First Lady, the position of First Lady was much more nationally prominent than it had been in the past. She took on the office with that in mind. She also had the task of redecorating the Civil War-damaged White House without any funds allocated from Congress… a task she accomplished mostly by bringing long-unused things out of storage in the White House attic. This was a move the contemporaries hailed as responsible for saving any good antiques left in the White House.

As a prominent First Lady, she was one of the first to be widely covered by national newspapers for her fashion, her family, her personality, and the social events she gave at the White House. She was also the first First Lady to officially be called “First Lady,” as during her tenure, the US press bestowed the moniker on the wife of the President.

Lucy invited some of the first African-Americans to the White House as guests. These were musicians of some national prominence. She was known for her kindness and invited all White House staff and their families, no matter how small the position, to spend Thanksgiving and Christmas with the Presidential family, even opening presents with them on Christmas morning. She encouraged staff members to take time off work to return to school, knowing they would have a job when they returned.

After one dinner, alcohol was banned from White House dinners during Hayes’s tenure as President, and early 20th century historians blamed Lucy, calling her “Lemonade Lucy,” because they knew she had signed a temperance pledge as a young woman. However, it was Rutherford’s decision to ban alcohol from the White House, since he believed they needed the Temperance vote to pass many of their legislative agenda items. Though Rutherford and Lucy did not partake themselves, they had served alcohol at dinners they gave when Rutherford was governor of Ohio. The dry White House was a purely political decision, but Lucy is forever associated with it.

Lucy got to enjoy some other “firsts” as First Lady. She was living in the White House when indoor plumbing and a telephone were installed in it for the first time. She not only was the first First Lady to enjoy a White House with indoor bathrooms, but she was also the first First Lady to use a telegraph, telephone, and phonograph while in office. She was the first truly modern First Lady.

She traveled across the continent with Rutherford when he was president and was the first First Lady to keep a public schedule of appointments separate from her husband. She encouraged Congress to complete the Washington Monument by providing the necessary funds. She also began the White House Lawn Easter Egg Roll tradition when Congress banned local children from rolling eggs on the lawn of the Capitol; Lucy invited them to the White House to do it instead.

Rutherford had promised Lucy he would only serve one term as president, and he kept that promise. Upon leaving the White House, they returned to their home in Ohio, where they became active in many local organizations and charities. They were well-known contributors to charities while in the White House, as well. They remained active in national affairs and were affectionate with one another, enjoying each other’s company.

Lucy died eight years after leaving the White House, after having a stroke at age 57. Rutherford died three years after her and was buried beside her. In 1915, they were both moved to the grounds of their home at Spiegel Grove, Ohio, which became the first presidential library. One of their dogs and two of their horses are buried under them, which fits in perfectly with their open and known love of animals.

Grave of Rutherford B. and Lucy Webb Hayes at Spiegel Grove, their home in Fremont, Ohio, United States. The property has been declared a National Historic Landmark. (Wikipedia)

People can visit Spiegel Grove today, including the grave of the Hayes’s and the library. It is owned by the Ohio History Connection and is open to the public, just as Lucy would have wanted it.