There have been nearly three and a half thousand military service members in the United States who have been awarded the prestigious Medal of Honor. Of these, only eighty-eight of them have been African Americans. Civil War hero William Harvey Carney was one of them.

Born as a slave in Norfolk, Virginia on February 29, 1840. Over the next several years, many members of his family were either freed by earning enough money to purchase their freedom, or, eventually, by the death of their owner. The records on the method William used to gain his own freedom are contradictory or non-existent, but most sources state he used the Underground Railroad, probably as a teenager, and joined the freed members of his family in Massachusetts.

A naturally curious boy who was eager to learn, William got involved in academics in Massachusetts, being taught to read and write in secret, because of the laws preventing African Americans from this pursuit. He decided on a career in the church, but the Civil War broke out before he could begin his ministry training. Instead, he decided that the best way for him to do God’s work at that time was to join the Union army and help free the slaves in the south.

William enlisted in March of 1863 and was assigned to Company C, 54th Massachusetts Colored Infantry Regiment. This was the first official regiment of African American soldiers recruited for the Union in the north. There were forty other African American soldiers in the regiment with him, including two sons of the famed Abolitionist leader, Frederick Douglass.

After a few months of training, William was sent to South Carolina with his regiment. There, on July 18, 1863, William and his regiment led a charge on Fort Wagner. The unit’s Color Guard was shot during the battle, and William, being just a few feet away at the time, ran to grab the American flag from the falling soldier.

William was seriously injured during his attempt to save the flag, being shot several times himself. Still, he refused to let the flag touch the ground, and managed to keep it aloft while he crawled to the top of the hill, where the walls of Fort Wagner stood. Any member of his regiment he saw along the way, he urged to follow him.

When he reached the fort, William planted the flag in the sand at the base of the fort and continued to make sure it was held upright until he was rescued. Witnesses say he was almost dead when he was found, and still holding the flag up so it wouldn’t touch the ground.

Even when he was rescued, he kept holding onto it, refusing to let his rescuers touch it. William held onto the American flag until he was brought to the temporary barracks of the Union army, where he finally relinquished it to another soldier.

William was seriously injured and nearly died after losing a lot of blood from the gunshots; however, he pulled through and survived, without ever letting the flag touch the ground. His actions on the battlefield that day inspired other soldiers who were involved in the charge, and his regiment became crucial to securing a victory for the north at Fort Wagner. William was promoted to Sergeant for his actions and bravery on the battlefield after he recovered.

He received an honorable discharge from the Army because of his wounds the next year. After the war, William went back to New Bedford, Massachusetts, and found a job maintaining the street lights of the city. Afterward, he became a mail carrier, a job he held for thirty-two years. He became a founding Vice-President of the New Bedford Branch Eighteen of the National Association of Letter Carriers in 1890.

He went on to marry Susannah Williams, and together, they had a daughter, Clara Heronia Carney.

On May 23, 1900, William was awarded the Medal of Honor for his bravery during the charge on Fort Wagner. Quite a lot of Civil War Medals of Honor were awarded decades after the actual war, some being awarded twenty or thirty or more years later, like William’s award. While other African Americans who fought in the Civil War had received the Medal of Honor before him, his actions that resulted in the award took place before theirs. Therefore, William is considered to be the first African American to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

The citation for his Medal of Honor reads:

“When the color sergeant was shot down, this soldier grasped the flag, led the way to the parapet, and planted the colors thereon. When the troops fell back he brought off the flag, under a fierce fire in which he was twice severely wounded.”

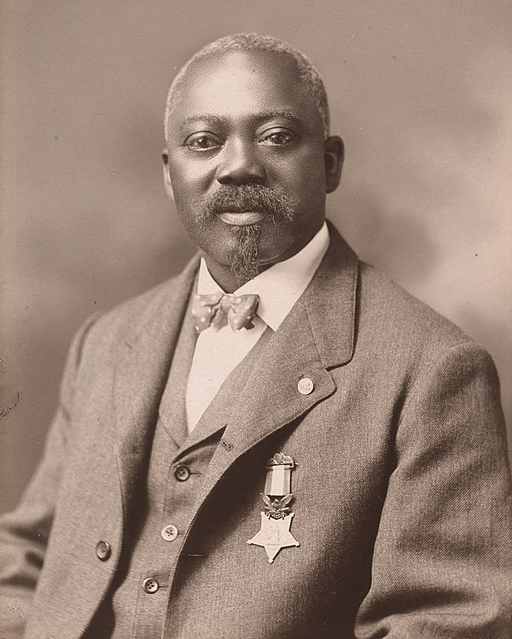

William Harvey Carney after the war, wearing his Medal of Honor (Wikipedia)

William lived out the rest of his life in Massachusetts, except for a few years spent out in California, and died at the Boston City Hospital on December 9, 1908, because of injuries he sustained in an elevator accident at the Massachusetts State House, where he was working for the Department of State. At the request of his wife and daughter, his body lay in state for a day at the Walden Banks funeral home on Lenox Street. He was then buried in the family plot at the Oak Grove Cemetery in New Bedford, Massachusetts. The Medal of Honor is engraved on his headstone.

Today, an elementary school in New Bedford is named after him, his face is on the Robert Gould Shaw monument, and his house in New Bedford is on the National Register of Historic Places.

William’s old regiment was disbanded ages ago but was recalled to duty in 2008. It now serves as a National Guard ceremonial unit that is present at honorary funerals and state events. It also marched in President Barack Obama’s inaugural parade.