In the 1930s and 1940s, as America faced the Great Depression and World War II, photography emerged as a powerful tool for documenting the struggles and resilience of everyday people. Through the lenses of pioneering photographers, the era’s challenges and triumphs were preserved in images that still resonate today. This was the beginning of modern documentary photography—a movement that recorded history and brought the human experience into vivid focus.

The Early Days: Photography as a Tool for Truth

Before the 1930s, photography had been around for nearly a century but was mainly used for portraiture and artistic compositions. Large cameras with long exposure times made spontaneous captures difficult, so photographs were often staged. As technology advanced, however, cameras became smaller and more portable, allowing photographers to capture life as it unfolded. Photography was evolving from a tool of art into one of truth-telling.

When the Great Depression hit in 1929, photography’s potential to document reality took on new significance. The economic collapse left millions of Americans struggling, and the government recognized that people needed to see, in a deeply personal way, the toll it was taking on citizens across the nation. This realization led to one of American history’s most significant photography projects.

The Farm Security Administration (FSA) and the Power of Documentary Photography

In 1935, as part of the New Deal, the U.S. government created the Farm Security Administration (FSA) to address rural poverty. Alongside programs to support struggling farmers, the FSA launched a photography project to capture the effects of the Great Depression on American life. Beyond simple documentation, the project was a way to sway public opinion and build support for New Deal programs by showing the human faces behind the crisis.

The FSA assembled a team of talented photographers, including Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Arthur Rothstein, Gordon Parks, and Ben Shahn. These photographers traveled across the country, focusing on impoverished rural areas, creating images that would define the era. Their mission was to reveal the depth of the crisis and make the struggles of millions visible and relatable.

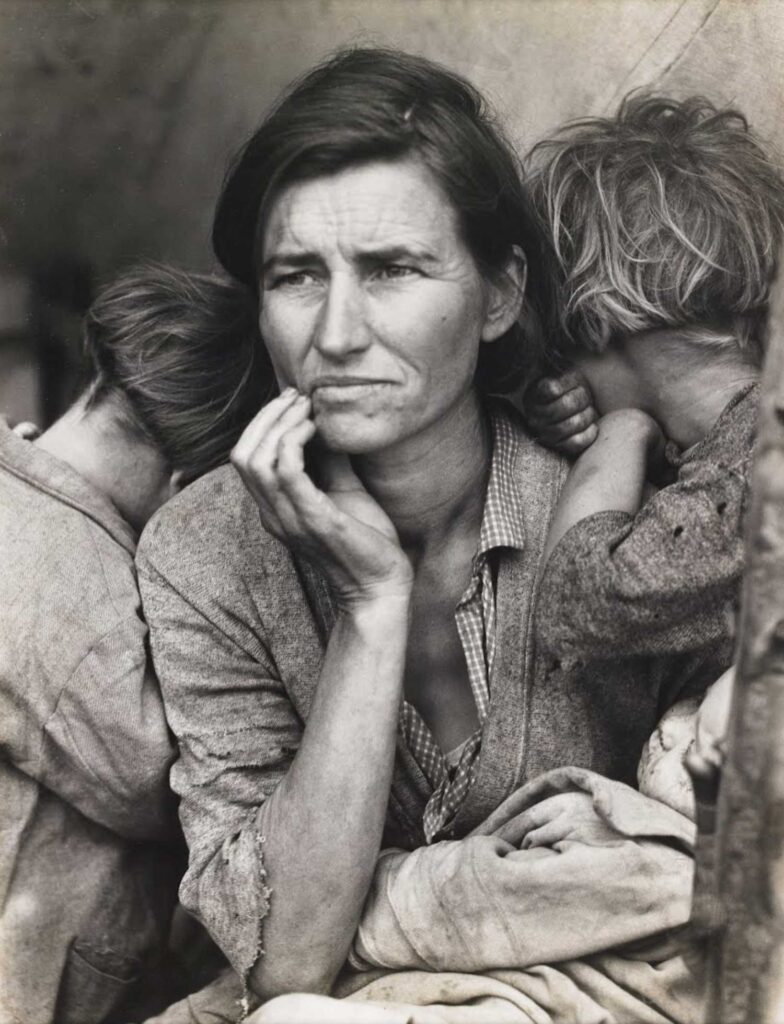

One of the most iconic images from this period is Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother,” a portrait of Florence Owens Thompson with her children clinging to her, gazing into the distance with worry etched on her face. The photograph became a symbol of the Great Depression, capturing the resilience and hardship of American families. Through such images, the FSA photographers brought the plight of ordinary people into focus, creating a powerful visual history that moved Americans and encouraged empathy and action.

The Rise of Photojournalism: Telling Stories Through Images

While the FSA focused on rural poverty, the concept of photojournalism—telling news stories through images—was gaining popularity. Magazines like Life and Look pioneered photo essays, combining powerful images with minimal text to convey stories as compelling as any written article. These photo essays brought a new immediacy to reporting, helping readers feel connected to events in a way that words alone couldn’t accomplish.

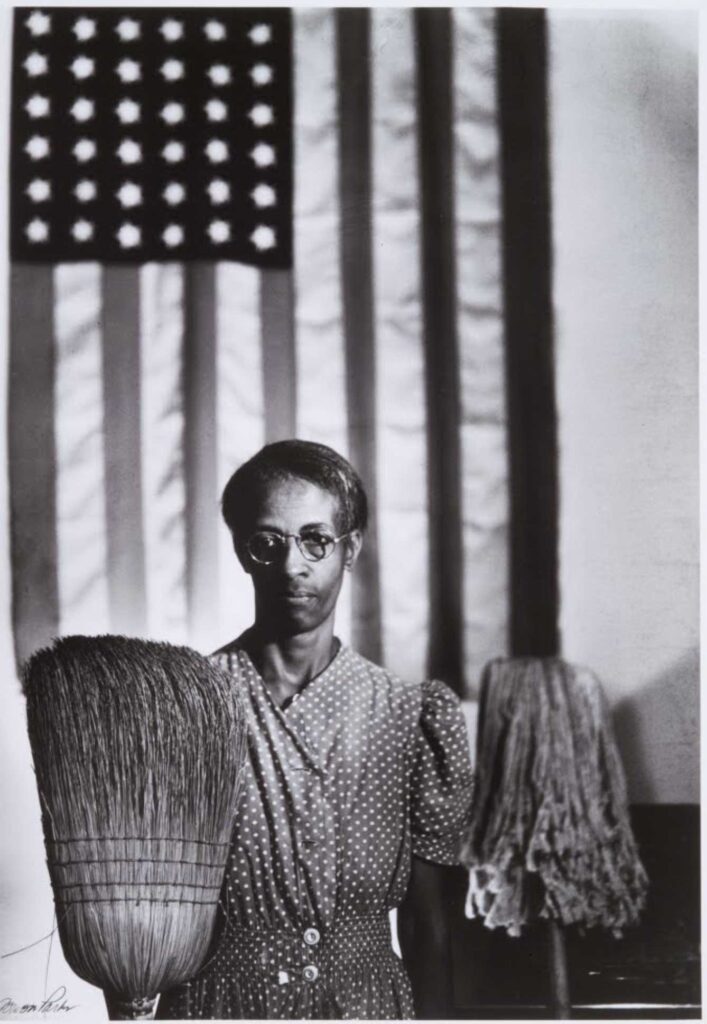

Gordon Parks, one of the first African American photographers hired by the FSA, brought a unique perspective to his work. In his famous photo “American Gothic, Washington, D.C.,” Parks captured a Black cleaning woman standing with a mop and broom before an American flag, a striking commentary on racial inequality in the nation’s capital. His work urged viewers to confront social injustice, pushing the boundaries of photography as a medium for social change.

Walker Evans, another FSA photographer, took a different approach. His images were often stark and unembellished, capturing scenes like empty storefronts, worn-out homes, and tired faces with a quiet dignity. Evans’s work is known for its simplicity and honesty, presenting people and places exactly as they were. His images from the American South, later published in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men with writer James Agee, remain some of the most powerful examples of documentary photography.

Photography During World War II: A New Perspective on Conflict

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, photography continued to evolve, capturing the harsh realities of global conflict. The government created the Office of War Information (OWI) to generate support for the war effort through media, including photography. Photographers like Margaret Bourke-White, Robert Capa, and W. Eugene Smith joined troops on the front lines, recording the devastation of war and the courage of those involved.

Margaret Bourke-White, known for her fearless approach, became one of the first female war correspondents. She documented everything from bombed cities to the liberation of concentration camps, capturing the resilience of soldiers and civilians alike. Her photographs brought the war’s impact into clear view for Americans back home, showing not just the battles but the profound human cost of the conflict.

Robert Capa’s work during WWII, especially his images of the D-Day invasion at Normandy, epitomized the raw intensity of war photography. Capa’s photographs, often blurred and chaotic, conveyed the terror and urgency of the invasion in a way that written accounts could not. His approach, staying close to the action, set a new standard for war photography, emphasizing the photographer’s role as both an observer and a participant in the events.

The Legacy of Depression and War Photography

The photography that emerged during the Great Depression and WWII did more than record history; it reshaped how people understood the power of images. These photographs were records and visual arguments, encouraging viewers to confront poverty, inequality, and the human toll of war. The work of Lange, Evans, Parks, Bourke-White, Capa, and others helped transform photography into a respected tool for truth and social awareness.

The impact of these photographers is still evident today. Many of their images are iconic, studied in classrooms, and exhibited in museums, reminding us of a time when a photograph could shift public opinion and inspire action. Their legacy endures in the power of modern photojournalism and documentary photography, which continue to play vital roles in shaping our understanding of current events.

A Lasting Impact: The Human Connection Through Photography

The Great Depression and WWII were pivotal moments in American history, and photography helped people witness and understand them in a deeply personal way. Through photographs, Americans saw the struggles of strangers in distant states and the courage of soldiers on faraway battlefields, creating an emotional connection that would become a hallmark of modern photography.

Today, the work of these pioneering photographers lives on as more than a historical record. Their images are windows into a generation’s resilience, complexity, and humanity. In viewing them, we witness history and share in the journey of those who came before us—a reminder that, while time moves forward, the human experience remains a shared story.

To deepen your understanding of documentary photography during the 1930s and 1940s, here are some insightful books:

Documenting America, 1935–1943

Edited by Carl Fleischhauer and Beverly W. Brannan, this book showcases photographers’ work under the Farm Security Administration and the Office of War Information. It features images by Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Gordon Parks, capturing the essence of America during the Great Depression and WWII.

American Photography and the American Dream

Authored by James Guimond, this book explores how photographers like Lewis Hine, Walker Evans, and Dorothea Lange depicted the American experience, intertwining photography with the nation’s evolving identity.

American Modern: Documentary Photography by Abbott, Evans, and Bourke-White

This volume examines the contributions of Berenice Abbott, Walker Evans, and Margaret Bourke-White, highlighting their roles in shaping documentary photography during the 1930s.

Bust to Boom: Documentary Photographs of Kansas, 1936–1949

Compiled by John C. Ewers, this collection presents photographs depicting Kansas’s economic and social conditions from the Great Depression through the post-war period, offering a regional perspective on national events.

A collaboration between writer James Agee and photographer Walker Evans, this book provides a profound look into the lives of tenant farmers during the Great Depression, combining evocative prose with compelling photographs.