Many genealogy pros recommend people new to family history research start at the 1920 census when beginning to use sources outside of their family members and heirlooms. This is because most people alive right now can trace their family back at least that far on their own, usually, because they personally know someone who was alive then (or know someone who knew someone). When you start with what you already know in genealogy, it makes the rest of the research easier to get into and gives you a better start on the road to being a rock star family historian.

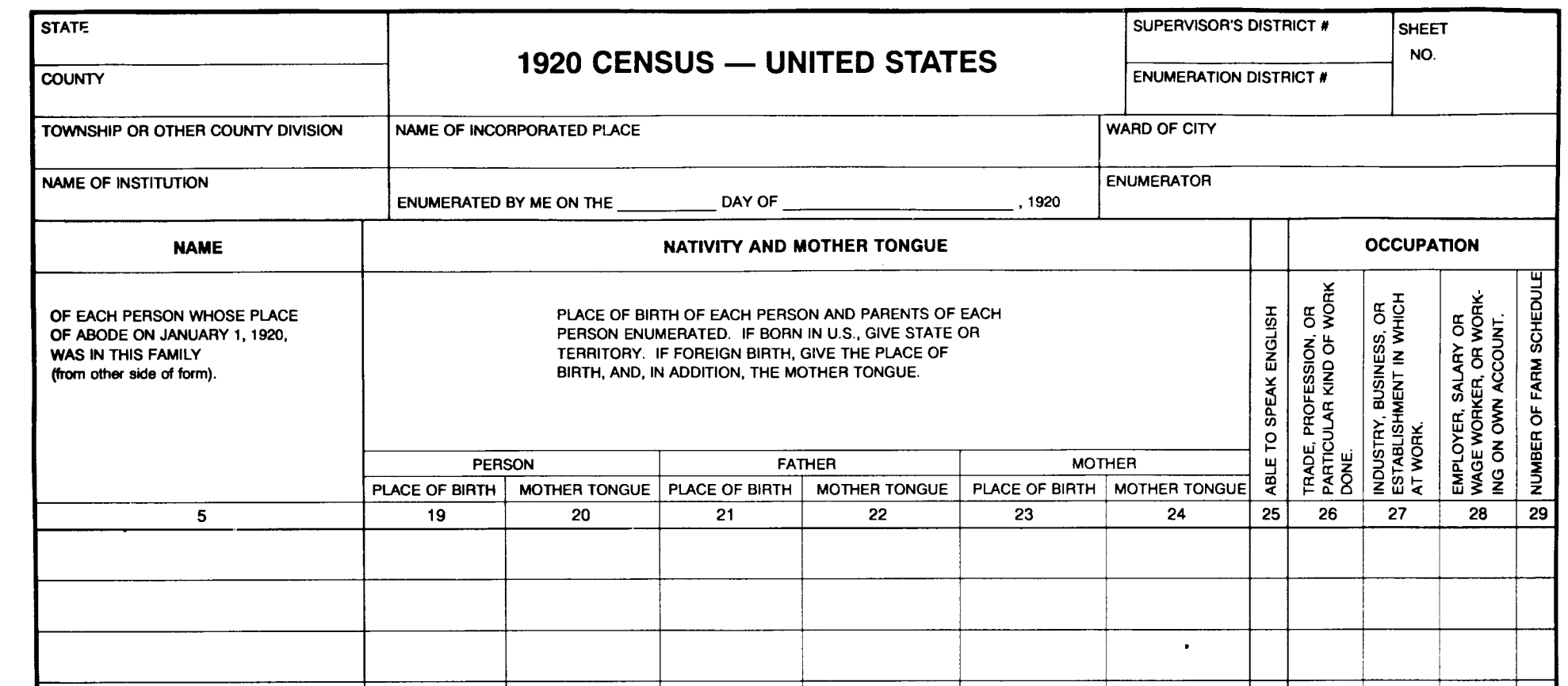

If you have used the 1920 census before, or are just considering using it for the first time, you will want to dig deeply into it. There is more genealogical information available on it than it at first appears. With a little attention to detail and knowledge about what certain information means to your family tree, you will find that the 1920 census offers far more genealogical gems than you initially thought. Here are some things to look for on the 1920 census, and how they can help further your genealogical research.

Check the Addresses

While the 1920 census included all of the usual information, such as names of household members, their ages, ethnicities, and relationships to the head of the household, house addresses were also listed. You will find street names and house numbers next to the heads of households on this census. It is valuable genealogical information that you can use to pinpoint exactly where your ancestors lived in 1920, and even visit there.

Addresses may have changed over the decades, with re-numbering and re-naming of streets, but you can find the correct address with local city and town records if this was the case with your ancestors. Most of the time, though, you will find addresses and street names are the same then as they are now. You can use the addresses to either visit the house in person and get a picture (or see the site where it once stood, if it is no longer there), or view it virtually on Google Maps. This is a wonderful way to have a look at things your ancestors saw every day, and get an idea of how they lived in 1920.

Your ancestors’ professions are listed on the 1920 census. If you did not previously know them, this is more information to let you get to know your ancestors better. You can also use the information to find the local company your ancestor worked for in whatever his or her job capacity was, and find out if the company still exists and has old employment records. These records can be quite useful to you in your genealogical quest for information on your ancestors’ daily and personal lives.

This is also the first census to record a profession called “own account.” Today, “own account” means someone who is working for themselves as a freelancer (not for oneself and tied down to a single location, such as store owner or baker).

New Regions Added

This was the first census to count the people living in American Samoa, Guam, and the Panama Canal Zone. This is great information for people with ancestors living in these areas who were not previously able to locate them or find out anything about their lives. If you find a missing ancestor or ancestral family in one of these locations, you can look at other record repositories for these areas to find additional important genealogical information on your ancestors.

Detailed Information on Immigration

In 1920, the United States was experiencing a high period of immigration, and arrivals at the famous Ellis Island and other ports were at an all-time peak. The 1920 census reflects this high level of immigration by asking detailed immigration questions. On it, you will find the year any immigrant arrived in the United States, whether or not they were naturalized when the census was done, their year of naturalization, and their native language. This information is wonderful for tracking down immigration records for your immigrant ancestors.

Women in Charge

The 1920 census lists far more female heads of household than any census before it. This reflects the changing economic and social nature of the United States, where the nuclear or extended family all under one roof was not always the only reality. Many women were widowed by WWI, divorced, abandoned by their spouses, or simply single by choice because they wanted to pursue a career, which was a real option for them by this time in history. So, when searching the 1920 census for your ancestors, do not always assume a man is going to be the head of the household. Look for women’s names as often as men’s, if you do not know the status of your family at this time in history.

Usual Place of Abode

With the 1920 census, enumerators began listing people as residing at their “usual place of abode,” not just where the enumerator happened to find them. In past censuses, people temporarily working away from home, traveling, or even visiting friends or neighbors for a short period of time would be listed there, not in their actual place of residence.

For enumeration purposes in the 1920 census, “usual place of abode” meant where a person usually slept. If someone was homeless or did not otherwise have a regular residence, only then were they listed as living where the enumerator found them. Enumerators had to ask each respondent if a household member were absent on a temporary basis; if they were, that person was listed with their usual household even if they were not there when the enumerator was there.

Some Information May be Sketchy

Enumerators for this census were not required to spell out a person’s whole name. They only had to write down the name the person gave them, which may have been just initials, or even a nickname. They also did not have to require proof of name, age, date of immigration, or anything else. All information was recorded based on what the respondent told them. If someone was lying or did not have the correct information available to them (and so was guessing, or made a mistake), this erroneous information was recorded on the census.

Also, no question about race was asked to anyone but was recorded based on what the enumerator believed a person’s race to be, going on the person’s appearance and the enumerator’s individual perception. So, when using the 1920 census, it is useful to use other sources to back up some of the facts presented on it.