John Morton was born in 1725 in Chester County, Pennsylvania, in Ridley Township. The township is today part of Delaware County. His father was also named John Morton and was a Finnish immigrant to the American colonies at a time when Finland was part of the Realm of Sweden. John’s father came to the colonies with his own great-grandfather (the younger John’s great-great-grandfather), Martti Marttinen. The name was later Anglicized to Morton. John’s mother was Mary Archer and was also of Finnish descent.

John was his father’s only son, and his father actually died before John was born, when his mother was still pregnant with him. When John was about seven years old, after a time of being raised by only his mom, his mom re-married to John Sketchley, who was a farmer of English descent. His step-father provided John with his education.

After he grew up, John married Ann Justis, who was a great-granddaughter of Finnish colonists. He and Ann would have eight children together, five girls and three boys. One of the boys, Sketchley Morton, was named after John’s stepfather, who raised him as his own.

John, his wife, and their children were active members of the Anglican Church in Chester County, Pennsylvania.

John began a political career early in his life. He was elected to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly in 1756 when he was only thirty-one years old. The year after this appointment, he was appointed as Justice of the Peace, and he kept this office until 1764. In 1765, John served as a delegate from Pennsylvania to the Stamp Act Congress.

John resigned from the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly in 1766 so that he could serve as sheriff of Chester County. In 1769, John was elected to the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly once more and was elected as its Speaker in 1775. At the same time, his legal career achieved its pinnacle in 1774, when he was appointed as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

The same year John achieved his appointment to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, he was appointed to the First Continental Congress, and then to the Second Continental Congress. He was part of the Pennsylvania delegation. In favor of independence, John cautiously helped move his delegation, and the people of Pennsylvania, toward this goal.

The Second Continental Congress agreed to draw up a declaration of independence in June of 1776, and the delegates from Pennsylvania were, at that time, divided on whether or not they agreed with the issue. John, along with Benjamin Franklin and James Wilson were in favor of independence, while delegates John Dickinson and Robert Morris were opposed to it. John actually took the most cautious approach of all, being uncommitted to either side of the issue until July 1, 1776, at which time he decided to become pro-independence and align himself with Franklin and Wilson. On July 2, 1776, when the final vote on adopting the Declaration of Independence was taken, Dickinson and Morris abstained from casting their votes, which allowed the Pennsylvania delegation to vote in favor of it. This was important, as the vote to adopt the Declaration of Independence had to be unanimous.

Most of the other delegates to the Congress signed the Declaration on August 2, 1776 (though a few signed sooner and some signed later), but John signed with the majority of the delegates on that day.

Later, while still serving on the Continental Congress, John was the chairman of the committee that wrote the Articles of Confederation, which was the first governing document of the new nation, before the Constitution was written several years later. John, though in charge of the committee that wrote the Articles of Confederation, passed away, most likely of tuberculosis, before the Articles were adopted.

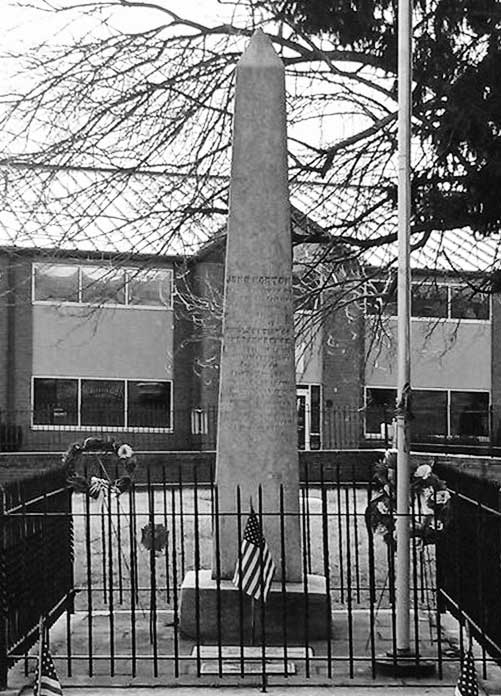

John was the first signer of the Declaration of Independence to pass away. He was buried in the Old St. Paul’s Church Burial Ground (aka the Old Swedish Burial Ground, in Chester, Pennsylvania. His grave was unmarked until October of 1845 when a group of his descendants put an eleven-foot marble obelisk there.

There is a rather lengthy inscription on the obelisk. The west side of the obelisk says:

“Dedicated to the memory of John Morton, A member of the First American Congress from the State of Pennsylvania, Assembled in New York in 1765, and of the next Congress, assembled in Philadelphia in 1774. Born A.D., 1724 – Died April 1777.”

The east side of the obelisk reads:

“In voting by States upon the question of the Independence of the American Colonies, there was a tie until the vote of Pennsylvania was given, two members of which voted in the affirmative, and two in the negative. The tie continued until the vote of the last member, John Morton, decided the promulgation of the Glorious Diploma of American Freedom.”

The south side of the obelisk says:

“In 1775, while speaker of the Assembly of Pennsylvania, John Morton was elected a Member of Congress, and in the ever memorable session of 1776, he attended that august body for the last time, establishing his name in the grateful remembrance of the American People by signing the Declaration of Independence.”

The north side of the obelisk says:

“John Morton being censured by his friends for his boldness in giving his casting vote for the Declaration of Independence, his prophetic spirit dictated from his death bed the following message to them: ‘Tell them they shall live to see the hour when they shall acknowledge it to have been the most glorious service I ever rendered to my country.”

John Morton Obelisk

The University of Turku established the John Morton Center for North American Studies in 2013. This center was established because the university felt the overall field of North American studies was fragmented, and that a national institute for it that taught one cohesive, unified area of the discipline was something the educational world needed.