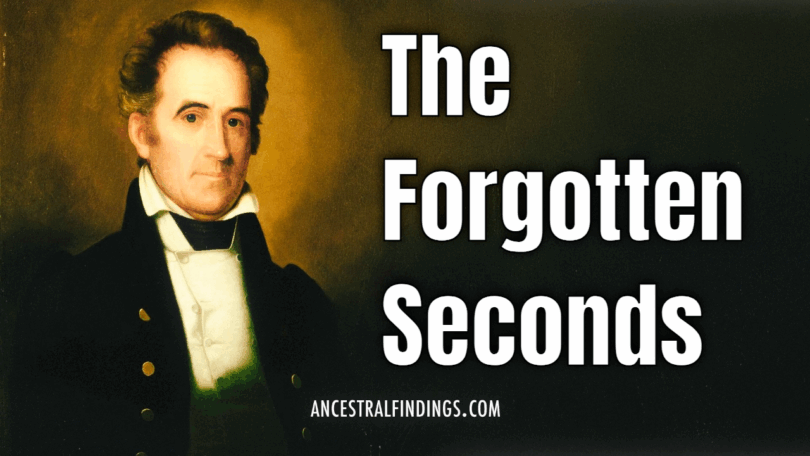

As we continue through our The Forgotten Seconds series—exploring the lives of vice presidents who never became president—we now turn to one of the most unusual figures ever to hold the office. Richard Mentor Johnson, a frontier-born politician from Kentucky, lived a life full of contradictions. Celebrated as a hero of the War of 1812 and known for his plain appeal to common voters, he was also scorned by many in his party for his controversial personal life and lack of discipline while in office. Though he rose to the second-highest post in the nation, Johnson never reached the presidency, and his legacy has largely faded from memory. His story begins on the western edge of Virginia and ends in political obscurity—but in between, it reveals a great deal about early American identity, race, class, and politics.

Early Ancestry and Family History

Richard Mentor Johnson was born on October 17, 1780, in what was then Louisa County, Virginia. His parents were Robert Johnson and Jemima Suggett Johnson. Both the Johnson and Suggett families had been part of Virginia’s planter society for generations. They were descended from early English colonists, and by the time Richard was born, both family lines had acquired land, wealth, and influence.

Robert Johnson, born in 1745, was a surveyor and a Revolutionary War veteran. In 1783, he moved his family west to the frontier lands of Kentucky, which was then part of the Virginia territory. He became one of the state’s early political leaders, serving in both the Kentucky House of Representatives and the Senate, and helping to draft Kentucky’s first constitution. He was a friend of Thomas Jefferson and shared his vision of an agrarian republic. His land acquisitions in what became Scott County, Kentucky, gave the family financial security and a high social standing in the area.

Jemima Suggett Johnson, born in 1742, came from the well-known Suggett family of Albemarle County, Virginia. She is often credited with instilling a strong sense of patriotism and moral responsibility in her children. She raised eleven of them, and several went on to hold public office. She was widely respected in Kentucky as a matriarch of one of the state’s most prominent families.

Richard had several politically active siblings. His brother, James Johnson, served in the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky. His other brother, John Telemachus Johnson, also served in Congress and later became a judge. Another brother, Benjamin Johnson, became a federal judge in Arkansas. Together, the Johnson brothers formed an influential political family that shaped regional and national policy in the first half of the 19th century.

Education and Entry into Public Life

Richard studied at Transylvania University in Lexington, Kentucky. At the time, it was the premier institution of higher education west of the Appalachian Mountains. He studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1802. He quickly opened a law practice and gained a reputation for plainspoken legal arguments and a strong rapport with working-class Kentuckians.

By 1806, Johnson was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He served for over a decade, establishing himself as an advocate for the western frontier, internal improvements, and support for veterans. His political views aligned with those of the Democratic-Republican Party, particularly in its defense of states’ rights and its opposition to strong centralized banking powers.

Military Career and the Battle of the Thames

Johnson’s military service during the War of 1812 became the defining chapter of his early fame. He raised a regiment of mounted volunteers and led them into Canada in 1813. At the Battle of the Thames, Johnson and his men played a decisive role in defeating British and Native American forces. During the battle, he was wounded and narrowly escaped death.

Johnson later claimed that he shot and killed Tecumseh, the Shawnee leader who had united Native tribes in resistance to American expansion. While the claim was never definitively proven, it became a significant part of his public image and earned him near-legendary status in western states. The slogan “Rumpsey Dumpsey, Colonel Johnson killed Tecumseh” would echo for years afterward.

Family, Marriage, and Controversy

One of the most striking and controversial aspects of Johnson’s life was his relationship with Julia Chinn, a mixed-race enslaved woman who lived on his estate. While many Southern politicians privately had relationships with enslaved women, Johnson did not hide his connection with Chinn. He referred to her as his common-law wife, treated her as the mistress of his household, and entrusted her with management of his estate during his absences.

Together, Johnson and Chinn had two daughters, Adaline and Imogene, whom he acknowledged as his children. He arranged for their education and attempted to secure advantageous marriages for them. In a time when interracial unions were not only illegal but taboo in much of the country, Johnson’s open acknowledgment of his family drew harsh criticism, even from within his party.

Julia Chinn died in 1833 during a cholera epidemic. After her death, Johnson continued to have relationships with women of color, including others who had been enslaved, and this further complicated his public reputation.

Vice Presidency and Its Challenges

In 1836, Johnson was nominated as vice president on the Democratic ticket with Martin Van Buren. Van Buren, formerly Andrew Jackson’s secretary of state and vice president, was the clear favorite for the presidency. But Johnson’s nomination proved divisive. Several Southern Democrats refused to support him because of his relationship with Chinn and his children. As a result, although Van Buren won the presidency, Johnson fell one electoral vote short of a majority.

According to the Constitution’s 12th Amendment, the vice presidency was then decided by a vote in the U.S. Senate. On February 8, 1837, Johnson was elected vice president by the Senate—a distinction unique in American history.

His term was filled with difficulty. Johnson was seen by many in Washington as more interested in Kentucky affairs than in national governance. He frequently returned home to manage his tavern business and estate, and as a result, he missed many Senate sessions, where he was supposed to preside. His lack of discipline and occasional eccentric behavior—such as reading newspapers or telling long stories during Senate proceedings—frustrated his colleagues.

Some saw him as a representative of common Americans, a man who never lost touch with his rural roots. Others believed he was an embarrassment to the administration and a liability to Van Buren’s image. By 1840, when Van Buren ran for re-election, the Democratic Party chose not to renominate Johnson. Van Buren ran without a running mate, and the ticket lost decisively to William Henry Harrison and John Tyler.

Return to Private Life and Final Years

After his vice presidency ended in 1841, Johnson returned to Kentucky. He remained active in Democratic politics and sought a return to national office. In 1844, he made an unsuccessful bid for the Democratic nomination for president. Though he received a few votes at the national convention, the party ultimately chose James K. Polk.

Johnson never regained national influence. In 1850, he won a seat in the Kentucky House of Representatives, where he served briefly before falling ill. He died on November 19, 1850, at the age of seventy. He was buried in Frankfort Cemetery in Kentucky.

Richard Mentor Johnson lived a life that reflected the tensions and contradictions of early 19th-century America. He rose from the Kentucky frontier to become a national war hero, a congressman, and vice president of the United States. His personal choices—especially his open relationship with Julia Chinn and his mixed-race daughters—set him apart from nearly every other public figure of his time, and they came at significant political cost.

As vice president, Johnson struggled to fulfill his duties, and his erratic behavior limited his effectiveness. Still, he holds a unique place in American history as the only vice president ever chosen by the Senate. His career declined quickly after he left office. Still, the story of his life offers valuable insights that I didn’t know were there into the political, racial, and cultural dynamics of his era.

Though largely forgotten today, Richard Mentor Johnson’s legacy remains relevant for what it reveals about the complexities of American leadership in the decades between the Revolution and the Civil War.