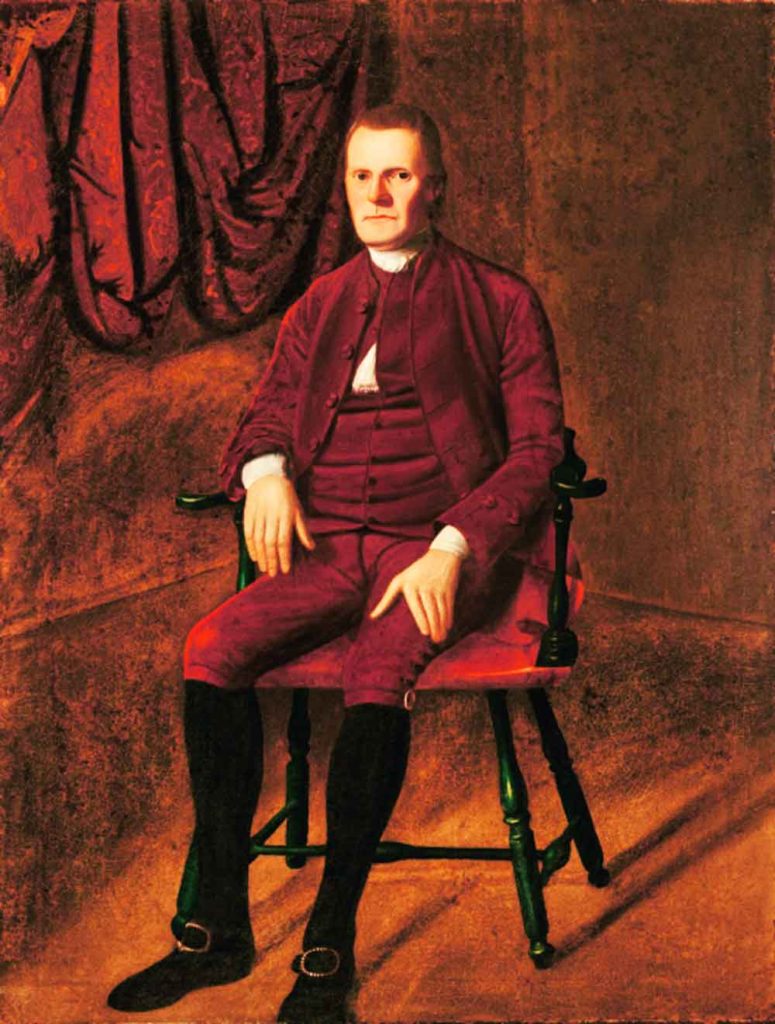

Roger Sherman was a signer of the Declaration of Independence from Connecticut. In addition, he was also a lawyer, and the only person to have signed all four of the “founding documents of the United States… The Continental Association, the Declaration, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution. He was also a signer on the 1774 Petition to the King.

Roger was born in 1721 in Newton, Massachusetts. His father, William Sherman, was a farmer. His mom, Mehitabel, was a homemaker. Roger’s parents moved with the family to the town of Stoughton, Massachusetts when Roger was two years old. Because his family was of modest means, Roger did not receive a formal education beyond the local grammar school and his father’s considerable library. Yet, he was eager to learn, and good at it, and was lucky enough to have a parish minister who had a Harvard education and who was willing to be a mentor in academics to young Roger.

In 1743, Roger’s dad crossed over to the other side. Roger moved with his mom and siblings to New Milford, Connecticut. There, he and his brother William opened the town’s first store. Roger immediately set about getting involved in the local community in both civic and religious affairs and was soon a leading citizen of the town. This lofty status allowed him to become the town clerk. Later, thanks to his excellent skills in mathematics, he became the county surveyor of New Haven County, Connecticut in 1749. In 1759, he became a provider of astronomical calculations for almanacs.

Roger married twice and had a total of fifteen children between the two wives. Thirteen of these children lived past childhood. His first wife was Elizabeth Hartwell, whom he married in 1749. She crossed over to the other side in 1760. Roger was a single widower for a time before marrying a second time. His second marriage was in 1763 to Rebecca (sometimes spelled Rebekah) Prescott. Seven of his children were from his first marriage, and eight of them were from his second marriage.

Without any formal legal training, Roger was encouraged by a local lawyer to take the bar exam, which he did, and was admitted to the Bar of Litchfield, Connecticut in 1754. While studying for the bar, he wrote a treatise called A Caveat Against Injustice and was selected to represent New Milford at the Connecticut House of Representatives twice, from 1755 to 1758 and from 1760 to 1761.

In 1762, Roger was appointed as Justice of the Peace, and in 1765 was appointed as judge of the court of the common pleas. The following year, he was elected to the Governor’s Council of the Connecticut General Assembly, where he served until 1785. In addition, Roger served as Justice of the Superior Court of Connecticut from 1766 to 1789, after which he left to serve in the US Congress.

Among his other impressive accomplishments, Roger was appointed as treasurer of Yale College, and the college awarded him with an honorary Master of Arts degree. He became a professor of religion there for many years and engaged in correspondence on religious issues and themes with some of the leading theologians of the time.

While serving on the Continental Congress in 1776, Roger, along with George Wythe and John Adams, was a member of a committee that was responsible for establishing guidelines for US Embassy officials in Canada. Also while serving on the Continental Congress, Roger became a signer of the Declaration of Independence, although his hope had been for reconciliation with Great Britain.

Roger was elected Mayor of New Haven, Connecticut in 1784, which was an office he held for the rest of his life.

Of all of his impressive roles in forming the United States of America, Roger Sherman is perhaps best known as being one of the most influential members of the Constitutional Convention. While he did not speak much at the convention, being known as a “terse, ineloquent speaker,” and also being the second eldest member there (at sixty-six years of age, only the eighty-one-year-old Benjamin Franklin was older), Roger was still one of the most active members of the convention. Roger made one hundred sixty motions or seconds in reference to the Virginia Plan (while his opponent in the Plan, James Madison, made one hundred seventy-seven motions or seconds on the matter).

When he came to the Constitutional Convention, Roger, like most other members, was not planning on creating a new constitution. Instead, he was there to revise the Articles of Confederation, of which he was a signer. When a new, bicameral legislature was proposed, he was against it, preferring a unicameral one as they had with the Articles. Roger said,

“The problem with the old government was not that it had acted foolishly or threatened anybody’s liberties, but that it had simply been unable to enforce its decrees.”

Roger also believed that the weak central government set up by the Articles was fine as it was, and only needed to be tweaked so that it was more effective at raising revenue and at regulating interstate commerce.

Additionally, Roger said, in defending a unicameral legislature, said that the large states had not “suffered at the hands of small states on account of the rule of equal voting.” When Roger accepted that the Convention was going to institute a bicameral legislature, he immediately went to work organizing compromises and deals in order to get some of his desired legislation included in the new constitution.

Roger crossed over to the other side in 1793 after being ill for approximately two months with typhoid fever. This was the official diagnosis. The Gazette of the United States, about a month after Roger’s crossing, published a report that said that his doctor believed that Roger’s liver was the origin of his malady. Based on contemporary reports, though, his symptoms were equal to those of typhoid.

Roger was buried at the New Haven Green cemetery. Later, when that cemetery was moved in 1821, Roger was moved with it, to the new Grove Street Cemetery. That is where he can be found today.