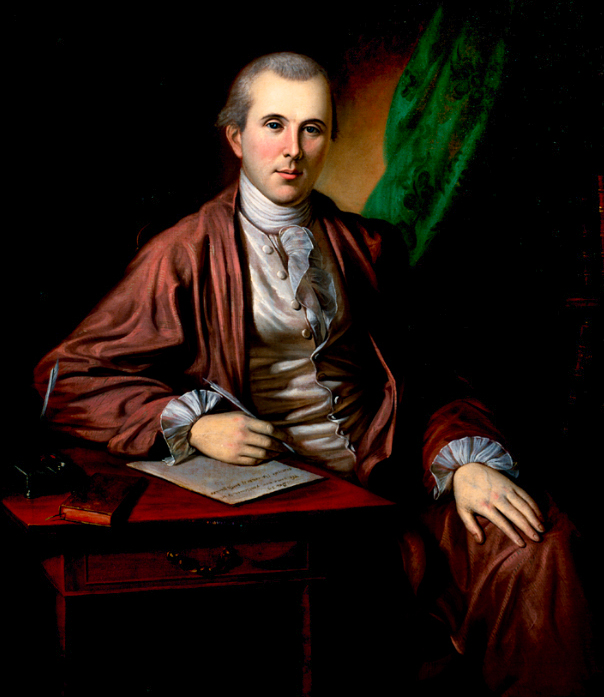

Benjamin Rush was born in January of 1746 in the township of Byberry in Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania. His parents were John Rush and Susanna Hall. Benjamin was the fourth of seven children born to his parents. John Rush crossed over to the other side when Benjamin was only five years old, which left his mom alone to care for the family. She operated a country store. When he was eight years old, Benjamin was sent to live with an aunt and uncle to receive his education. Along with an older brother, Jacob, Benjamin attended a school that later became the West Nottingham Academy.

Later, Benjamin attended the College of New Jersey (now known as Princeton University), graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree when he was fourteen years old. He apprenticed with Dr. John Redman in Philadelphia from the ages of fifteen to twenty. After that, he went to Scotland to attend the University of Edinburgh, where he earned a medical degree in 1768. While studying in Scotland, and on his subsequent European tour after graduating as a medical doctor, Benjamin became fluent in French, Italian, and Spanish. Benjamin also befriended the Earl of Leven and his family while studying for his medical degree, earning him friends in high places.

When Benjamin sailed back to the American colonies in 1769, he opened a medical practice in Philadelphia and also became a professor of Chemistry at the College of Philadelphia. Benjamin was elected to the American Philosophical Society and served as its Curator, Secretary, and Vice President at various times. He eventually published the first American chemistry textbook.

In January of 1776, Benjamin married Julia Stockton, who was a daughter of Richard Stockton (who was a fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence along with Benjamin). Julia’s mom’s name was Annis Boudinot. Benjamin and Julia had thirteen children together, nine of whom survived past childhood.

As a doctor, Benjamin was active in his local chapter of the Sons of Liberty. Because of his membership in that group, he was appointed to the provincial conference that was called to send delegates to the Continental Congress. In 1776, Benjamin was selected to serve on the Congress himself. Benjamin arrived at the Congress in time to vote on and sign the Declaration of Independence. He also represented Philadelphia at Pennsylvania’s Constitutional Convention and consulted with Thomas Paine when the latter was writing his highly influential pamphlet, Common Sense.

While serving on the Continental Congress, Benjamin was on its medical committee. In this capacity, he went with the Philadelphia Militia on some of their campaigns after the British occupied Philadelphia and most of New Jersey, acting as a field doctor for the soldiers. In fact, Benjamin is depicted as serving in the Battle of Princeton in the painting, The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777, by American artist John Trumbull.

When Benjamin went into the field, he found that the Army Medical Service was in chaos. There were the expected military casualties, yes, but also unusually high losses of soldiers from typhoid, yellow fever, and other common camp maladies. There were disputes between the two primary Army doctors, Dr. John Morgan and Dr. William Shippen, Jr., as well as a poor stock of medical supplies, and no real guidance from the Congress’s Medical Committee. In spite of these challenges, Benjamin accepted an appointment from the Congress as Surgeon General of the middle department of the Continental Army.

While in his job as Surgeon General, Benjamin wrote the Directions for Preserving the Health of Soldiers, which was the founding written document of American preventive military medicine, and was re-published many times over the decades, as late as 1908. Benjamin eventually resigned as Surgeon General in 1778, after he garnered controversy for becoming a Revolutionary whistleblower, reporting on the way Dr. Shippen misappropriated food and wine intended to strengthen the soldiers in military hospitals, and that Dr. Shippen also underreported the deaths of soldiers, and did not visit the military hospitals that were under his command.

Benjamin accomplished many things in his life. In fact, it was a life full of impressive accomplishments. In addition to his medical and political roles, he was also a professor, not only of Chemistry but later of Medical Theory and Clinical Practice at the University of Pennsylvania. Benjamin opposed slavery, advocated for free public schools, and pushed for improved education for women. In addition, he wanted a more compassionate and enlightened penal system in the new United States.

In addition, he was one of the first American doctors to make a serious and genuine study of the mind, coming up with a primitive and inaccurate, but groundbreaking for its time, theory of mental conditions. One of its hallmarks, which made it stand out from former, less enlightened theories, was that the mentally ill were humans and not sub-human animals. He also believed mental illness could be partial, and that engaging in meaningful work could help treat and sometimes cure it. Benjamin is considered one of the founders of American psychiatry. In 1965, the American Psychiatric Association named him the “father of American psychiatry.”

In 1812, Benjamin helped to re-establish the estranged friendship between Thomas Jefferson and John Adams by encouraging the two men to write to each other again as they used to.

Benjamin crossed over to the other side of typhus fever at the age of sixty-seven in April of 1813 and was buried in the Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia, not far from the final resting place of fellow Founding Father, Benjamin Franklin. Later, his wife Julia was buried there beside him. At the time of his crossing, Benjamin was the most well-known doctor in America.

A faithful Christian who believed Bibles in public schools should be mandatory, and that the federal government should supply a Bible to every American household that did not have one, at public expense, the plaque that marks the stone where he is buried reads:

“In memory of

Benjamin Rush MD

he died on the 19th of April

in the year of our Lord 1813

Aged 68 years

Well done good and faithful servant

enter thou into the joy of the Lord”

Benjamin’s wife’s plaque reads:

“Mrs Julia Rush

consort of

Benjamin Rush MD

Born March 2, 1759

Died July 7, 1848

For as in Adam, all die, even so in Christ

Shall all be made alive”