By the time you reach the modern era, birth records feel straightforward. You search an index, order a certificate, attach it to your tree, and move on. In real research, modern systems still create plenty of confusion: privacy restrictions block access, jurisdictions do not match the family story, indexes hide key details, and late or amended records complicate what you think you found. The difference now is that there are more paths to the answer. If you know how modern birth record systems are built, and you approach them with a proof mindset, you can usually get to solid birth evidence even when the official certificate is not available to you.

This article pulls the whole series together. The first article explained why birth documentation began in families, faith communities, and local record books. The second article traced how parish systems and early civil registration overlapped and why coverage varies so much. Now the focus is practical: how to find modern birth records, how to work within restrictions, how to use substitutes, and how to turn what you find into a conclusion you can trust.

Start With a Clear Target Before You Search

Modern record sets are big, and “birth record” can mean several different things. Before you search, define the target in a single sentence:

I am trying to find evidence that Name was born on about Date, in Place, to Parent Names.

Then add two more lines that guide your choices:

Best case: an original or certified birth record created near the time of birth.

Acceptable alternatives: a church baptism, delayed record, hospital record, Social Security application, passport application, early school record, or other document that reliably states birth details.

This keeps you from wandering through indexes without a plan. It also keeps you from treating the first thing you find as the answer when it is only a clue.

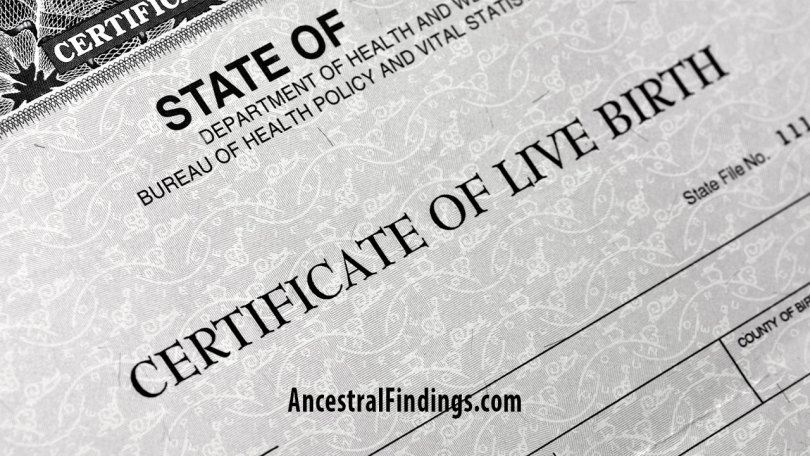

Know Where Modern Birth Records Live

Modern birth records usually sit under a civil authority, but “civil authority” can mean different levels depending on location.

Town or city registrar.

County clerk or county health department.

State or provincial vital records office.

National civil registry in some countries.

In the United States, birth certificates are generally held by state vital records offices, often with county level copies depending on state practice. In other countries, the local civil registry may be the primary source, with national indexes or duplicate holdings.

The key is jurisdiction at the time of birth. If a county split or a city annexed an area, the record may be filed under the jurisdiction that existed on the date of the birth, not the modern map you are looking at today.

Understand Access Restrictions and Work Around Them Legally

Modern birth records are often restricted for privacy. Many jurisdictions limit access to the person named on the record and close relatives, and they may require proof of relationship. That can stop genealogists cold if they assume the certificate is the only route.

When access is restricted, you switch strategies. Your goal becomes one of these:

Get an authorized copy through a qualified relative, if possible.

Get a non certified informational copy, if the jurisdiction offers it.

Use index information as a lead and then build proof through alternative records.

Use substitutes that have fewer restrictions and still provide reliable birth details.

The important point is that restrictions do not end research. They change which sources you use to prove the same facts.

Use Indexes as Finding Aids, Not Final Evidence

Indexes are extremely useful, but they are not the record. They are an interpretation of the record, and they can hide the best clues.

Common index problems include:

Misspellings and phonetic spellings.

Wrong dates due to transcription errors.

A child listed under a different surname than expected.

A record filed late or under an unexpected jurisdiction.

Missing fields, such as the mother’s maiden name, which might be present on the certificate but not in the index.

Use indexes to locate candidate records. Then pull the image or order the certificate when possible. If you cannot get the image, treat the index as a clue and look for a second source that confirms the same birth details.

Expect Modern Complications: Delayed, Amended, and Corrected Records

Modern systems did not eliminate messy records. They created new types of complexity.

Delayed birth registrations can be created years later, supported by affidavits and older documents. These can be excellent, but you need to look at what they were based on.

Amended birth records can change names, parent information, or other details. Sometimes amendments are minor corrections. Sometimes they reflect adoption, legitimation, or legal name change.

Corrected records may have marginal notes or separate amendment forms.

When you see any sign that a record was delayed or amended, treat it as a case file. Look for supporting documents referenced in the record. The supporting evidence is often where the real genealogical value is, especially if it includes affidavits by relatives or copies of older church entries.

Build a “Modern Birth Record Search Ladder”

When the ideal record is not available, you move down a ladder of substitutes. The goal is to collect enough high quality evidence to make a reliable conclusion, even without the original certificate.

Here is a practical ladder you can apply in most cases.

- Birth certificate or birth register entry, created near the time of birth.

- Baptism or christening record, especially one recorded close to birth.

- Hospital or physician record, if accessible through archives or family papers.

- Social Security application or claim records that contain self reported birth details, often supported by documentation at the time of application.

- Passport applications or other government identity applications where birth details were required.

- Marriage records that state age, birth date, and birthplace, sometimes with parents’ names.

- Death records and obituaries, useful but often weaker because they rely on an informant who may not know all details.

- Census records, which are great for building a birth year range and tracking consistency over time, but usually not strong enough alone.

- School, church membership, and cemetery records, which can help confirm identity and timeline.

The best practice is to use at least two independent sources when a certificate is not available. Independence matters. A death certificate and an obituary might both come from the same informant, so they do not count as two independent confirmations in the way a baptism entry and a Social Security application might.

Handle the Most Common Modern Problems

Wrong place of birth

Many people say they were born in the nearest large town even if the birth happened in a smaller community or rural area. Start with the family’s residence at the time, then search nearby jurisdictions and hospitals, not only the place named in later records.

Name changes and surname shifts

Children may appear under the mother’s surname, a stepfather’s surname, or a later standardized spelling. Search using flexible spellings and consider searching by parents’ names, not only the child’s name.

Multiple people with the same name

Use parents, residence, and sibling patterns to separate them. Modern birth records often include parents’ ages and birthplaces, which helps, but you still need to verify through additional records.

Late reporting

If you cannot find a record in the expected year, expand the search window and check for delayed registration. Also check whether the jurisdiction indexed by filing date rather than birth date.

Jurisdiction changes

If the area reorganized, check where the records were sent after a county split or a city annexation. Sometimes older records were moved to a new office, and sometimes they stayed with the original office.

Turn What You Find Into a Proof Style Conclusion

This is where the whole series comes together. Earlier eras taught you that “birth records” are not one thing. They are evidence. Modern systems give you more evidence types, but you still need to assemble them into a conclusion that holds up.

A simple proof approach looks like this:

State the claim: Name was born on Date in Place, child of Parents.

List your best evidence first, preferably created near the time of birth.

Explain any conflicts. If one record says 1902 and another says 1903, address why. Maybe the person did not know their exact date. Maybe the informant was guessing. Maybe the record was delayed.

Show why the identity is correct. Explain how you know the record belongs to your ancestor and not someone else with the same name, using parents, residence, or sibling links.

Finish with a clear conclusion that ties the evidence together.

You do not need to write a formal proof argument every time, but the mindset helps you avoid attaching the wrong birth record to the wrong person, which is one of the most common errors in online trees.

Closing

Birth records began as family memory, became institutional habit through churches and communities, and eventually became standardized civil systems. That history is not only interesting. It is practical. It explains why you sometimes find a beautiful certificate, sometimes find only a baptism entry, and sometimes have to build birth proof from several sources.

When you approach modern birth research with a plan, a jurisdiction aware search, and a ladder of substitutes, you stop treating restricted or missing certificates as a wall. You treat them as a signal to change sources. That is the real skill behind successful genealogy research: matching your methods to the way records were actually created and preserved.

If you can consistently do that, birth records become more than a starting point. They become a tool for proving identity, connecting generations, and building a family history you can trust.