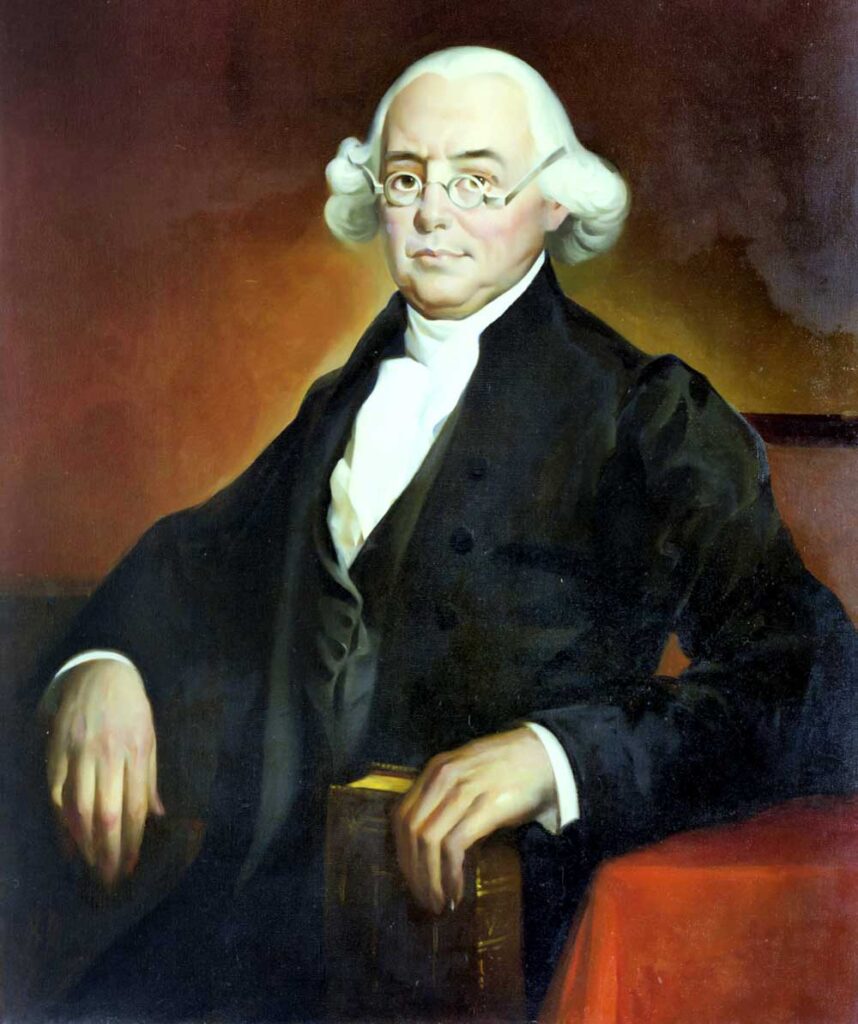

James Wilson was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Born in Scotland in 1742, James was elected to the Continental Congress twice, served at the Constitutional Convention that produced the US Constitution, served as an Associate Justice on the US Supreme Court (one of the six original justices appointed there by George Washington), and taught law as a professor at the University of Pennsylvania (where he taught the first course on the new US Constitution to President Washington and his cabinet).

James was the son of William Wilson and Alison Landall, the fourth of their seven children. His parents were farmers near Ceres, Fife, Scotland. They were also Presbyterians. James studied at St. Andrews University, Glasgow University, and Edinburgh University but did not graduate from any of these. James studied the popular Enlightenment thinkers of the day and also, like most Scotsmen, played golf.

After leaving university and full of new ideas from the Scottish Enlightenment, James left Scotland for the American colonies in 1765, settling in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Bringing letters of introduction with him to assist him in starting his new life, James was able to become a tutor and then a professor at the Academy and College of Philadelphia (which is now known as the University of Pennsylvania). James petitioned the university for a degree since he was teaching there, and was awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree several months after making his petition.

Whilst tutoring and being a professor, James was also studying law at the office of future fellow Signer, John Dickinson. This study allowed him the knowledge necessary to be admitted to the bar in Philadelphia n 1767. Once admitted, James set up his own law office in Reading, Pennsylvania, and began practicing as a lawyer. It turns out, that James was an excellent attorney, and his office became extremely successful. James earned a small fortune off of it in just a few years, and this fortune allowed him to purchase a farm near Carlisle, Pennsylvania. In addition to being a lawyer, in which work he took cases in eight counties near Reading, James was a founding trustee of Dickinson College and a vice-president of the American Philosophical Society. James also wrote on theological matters, with his religious beliefs seeming to move around the Christian spectrum for most of his life. He did, though, always seem to subscribe to some form of Christianity.

James married Rachel Bird in 1771. She was the daughter of William Bird and Bridget Hulings. Together, James and Rachel had six children, consisting of four sons and two daughters. Rachel crossed to the other side in 1786. James re-married in 1793 to Hannah Gray, the daughter of Ellis Gray and Sarah D’Olbear. Together, they had a son named Henry, who crossed to the other side at four years of age. After James crossed, Hannah re-married to Doctor Thomas Bartlett, a widower with two daughters, and they had a daughter together named Caroline.

In 1774, James published a pamphlet called “Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament.” James argued in the pamphlet that Parliament had no authority in the American colonies because the colonies did not have representation in Parliament. James believed that all political power was derived from the people. Still, he thought the colonies should maintain their allegiance to the King, even while making their own laws. This was a similar view to that taken by John Adams and Thomas Jefferson at that time.

James was commissioned as a colonel in the Fourth Cumberland County Battalion in 1775 and rose to the rank of brigadier general of the Pennsylvania State Militia after Pennsylvania became a state.

James was appointed to the Continental Congress as a delegate from Pennsylvania in 1776 and was a steadfast believer in independence at that time. Still, he believed his duty as a delegate was to vote the will of the people of the colony. So, he took several more polls of his constituents before voting in favor of independence at the Congress. As a part of the Continental Congress, James became a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

James left the Continental Congress in 1777. In 1787, he served at the Philadelphia Convention, where he was a member of that group’s Committee of Detail. This convention produced the first draft of what would become the US Constitution. James was the principal designer of the executive branch of the federal government, which includes the US Presidency. As a politician and designer of a new nation, James was a staunch believer in popular control of the government, a strong national government, and state representation in Congress proportional to its population.

With Charles Pinkney and Roger Sherman, James proposed the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted each slave in the new nation as three-fifths of a person for Congressional representation purposes. Also, even though he preferred the US President to be elected directly by the people, James was the one who proposed the use of an electoral college, which provided the basis for the Electoral College we still use today. In addition, he opposed the Bill of Rights.

In 1790, he played a large role in writing the Pennsylvania state constitution.

James was one of the first associate justices on the US Supreme Court, being appointed to it by George Washington in 1789.

Despite these incredible successes in his life, James suffered financial setbacks in his later years, thanks primarily to unstable economic conditions in the new United States and bad personal investments. He was even briefly imprisoned in debtors’ prisons in New Jersey and North Carolina, where he was able to continue to perform his duties as a Supreme Court justice. His son, Bird, paid his debts to get him out of debtor’s prison, so he didn’t have to be there long. James complained of creditors hounding him like wolves. It was probably both a humiliation and a seeming slap in the face after all he’d done to create the new country everyone was enjoying.

While visiting a friend in North Carolina in 1798, James experienced a bout of malaria and crossed to the other side of a stroke not long after. He was only fifty-five years old at the time. James was the first US Supreme Court justice to cross to the other side.

James was buried at the Johnston Cemetery on Hayes Plantation near Edenton, North Carolina, but in 1906 was moved close to his first wife, Rachel, to the Christ Churchyard in Philadelphia.