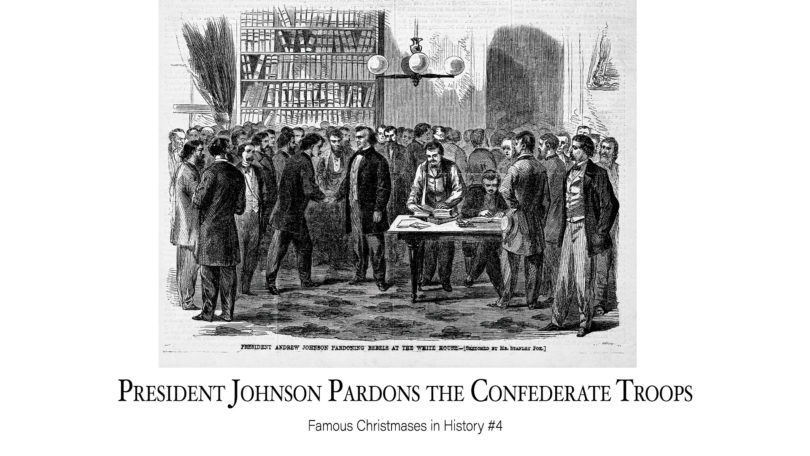

Another famous Christmas was three years after the end of the US Civil War. This was when then-US President Andrew Johnson decided to give a special Christmas gift to a select group of people. With Proclamation 179, which was issued on Christmas Day in 1868, President Johnson gave every single former Confederate soldier amnesty in the form of a pardon.

This was a big deal, as after the Union won the Civil War, the Confederate soldiers, officers, and anyone who had helped them in their cause in any way were technically considered traitors to the United States. Considering convicted traitors were usually executed in those days, the fact that no Confederates had even done any jail time to that point—with the exception of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who got a brief stay behind bars, and then a quiet retirement of freedom—was nothing short of a political miracle. Still, with no declaration of official amnesty, all of those former Confederate soldiers were left wondering for years what the US government would ultimately decide to do with them.

The general issuance of amnesty that President Johnson provided was the fourth item in a series of proclamations made since the end of the war that was intended to rehabilitate the former Confederate soldiers into US society once more. The first item was established in May of 1865, immediately after the end of the war. The previous items had done things like give legal and political rights (such as to vote in federal elections) back to the former Confederate soldiers in exchange for them signing oaths of loyalty to the United States. Still, there was no overall pardon of the Confederates, and there were fourteen classes of Confederates who were not initially given any restored rights after the war.

Some of the classes of Confederates who had been exempt from previous restorations of rights included officers in the Confederate army, members of the Confederate federal government, and Confederate soldiers with property valuing more than $20,000. These people were left in a kind of political limbo, where nothing had been done against them yet, but their rights had not been restored, and no agreement existed that no actions would be taken against them for their participation on the Confederate side of the war at some future time. Even the soldiers who had had some of their rights restored still did not have an official pardon, which meant there was always the possibility the US federal government may decide to take some punitive action against them at some point.

So, needless to say, those who had fought for or supported the Confederacy in any way were a bit tense in the years following the end of the Civil War. They simply did not know what the US government planned to do with them, so it was a challenge for them to make any plans for their futures or those of their families. The pardon of all Confederates that President Johnson issued on Christmas Day in 1868 gave a final and unconditional forgiveness to them, including the formerly exempt groups, and allowed the country to move forward as one united nation.