If there’s one piece of Ohio history that is too often overlooked, it’s the Battle of Fort Fizzle. This “battle,” otherwise known as the Holmes County Draft Riots, really was more of a small riot, one that occurred in Holmes County, Ohio during the Civil War. Even though we don’t hear much about the Battle of Fort Fizzle, back then, it was quite a prominent event, something so big that quiet little Holmes County stood out on a national level. In fact, Fort Fizzle loomed so large that for a time, it received national attention much in the same vein as the New York Draft Riots.

And the draft is what started the whole thing, too. During those times, there were a lot of tensions and a few events that led up to the Battle of Fort Fizzle. Let’s get started with what led to the Battle of Fort Fizzle, and then you’ll get to learn all about the battle itself!

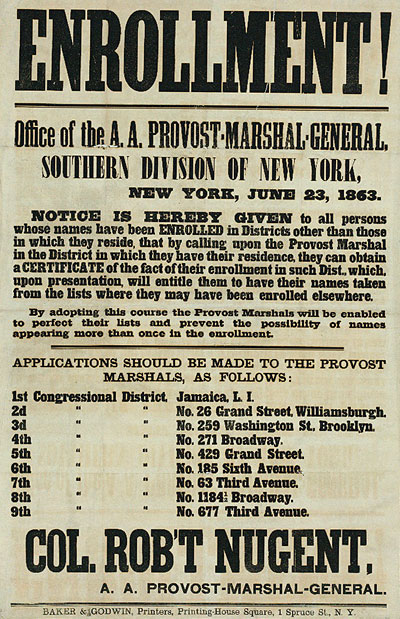

It All Started with the Enrollment Act

If there was a catalyst that led up to the Battle of Fort Fizzle, it was the Enrollment Act, which is also sometimes referred to as the Civil War Military Draft Act. The Enrollment Act was a piece of legislation passed by Congress and then signed by President Abraham Lincoln on March 3, 1863.

As the name suggests, this piece of legislation was a draft. By this point, the Civil War had been going on for almost two years, and the Union Army needed fresh manpower to keep fueling the warfront. The legislation called for a pretty extreme draft, too. It required all men between the ages of 20 and 45—both citizens and immigrants who had filed for citizenship—to enroll in the Union Army. With this came quotas established by federal agents, which meant that every congressional district within the Union had to submit a certain number of troops.

The Enrollment Act was designed as a replacement for the Militia Act of 1862, which was an act that allowed African Americans to serve in the Union’s army as soldiers and laborers. By this point in history, many were growing tired of the war effort, so when the Enrollment Act was put into law, it caused widespread unrest throughout the Union—almost a civil war within the Civil War!

Trouble Follows the Enrollment Act

One important thing to understand about the Civil War period, and how people within the Union responded to it, is this: Most assumed, in the leadup to the war and directly after the war started, that it wouldn’t last long. People figured the Civil War might go on for a few months or perhaps a year before the Union and the Confederation would find a way to resolve differences.

By the time the Enrollment Act was signed into law, though? The war had gone on for two years with no end in sight. People were frustrated, wishing they could go back to their usual daily lives without the threat of war and all the loss that comes with it, both of their loved ones and of things like homes, livelihoods, and more.

So when the Enrollment Act did become law, this caused a bit of fury, not just in Ohio, but everywhere throughout the Union. Certain tactics to circumvent being drafted became quite prominent. For instance, the Enrollment Act had a provision for “substitutions,” which meant that if a drafted man could provide a reasonable substitute, that substitute could enroll in the Union Army in his place.

This led to men actually creating new careers as “jumpers.” A jumper was someone who would offer to be a substitute for someone who had been drafted. He’d enroll in the draftee’s place—and then desert the Union Army, find another draftee, and substitute in the next draftee’s place. It was such a popular practice to avoid the draft that many military commanders would often see the same recruits over and over again.

Another provision that allowed men to circumvent the draft was the Enrollment Act’s provision for commutation. Under this provision, a man could pay $300 to avoid the draft. Both this and the substitutions provision were put in place so that pacifists could avoid going to war, but what actually happened was that these two policies caused a lot of resentment. Both provisions were founded in good intentions—but because of the way the Enrollment Act was structured, people took to calling the Civil War the “rich man’s war, poor man’s fight.” The end result was that only the wealthy could pay jumpers or the commutation fee to avoid the draft while those who didn’t have the means were forced to go to war.

About Fort Fizzle

Even though we don’t hear much about the Battle of Fort Fizzle, back in those days, it was a national-scale event. Today, there are many people, particularly among families in the region surrounding Holmes County, who are descended from those who were involved in Fort Fizzle.

Today, you can still visit the “battle” site, but there isn’t much left to see. Fort Fizzle is located in Holmes County, in a region called French Ridge on County Road 6. If you were to drive down this road, the one thing you would see to mark the historic event is an Ohio historical marker which was sponsored by the Ohio Bicentennial Commission, The Scotts Company, and the Ohio Historical Society. Here, you can read a little bit about what happened at Fort Fizzle.

Though this is unconfirmed, there may also be an old stone foundation remaining in the woods where Fort Fizzle used to stand. The interesting thing about the fort? It wasn’t actually a fort—just a stone house that, in the heat of the moment, rioters used as their base.

The Battle of Fort Fizzle

With the Enrollment Act, smaller uprisings had been occurring all over the Union, even in Ohio. On June 5, 1863, what would later become known as the Battle of Fort Fizzle got started.

And it all started with a thrown stone—the stone that started the battle if you will. On June 5, a man named Elias Robinson was in Holmes County. He was a traveling enrollment officer for the Union Army, and he was there to enforce the Enrollment Act. Tensions were already high due to the draft’s unpopularity, and when Robinson reached the Glenmont, Ohio area, people there thought he seemed rude.

An argument broke out between Elias Robinson and several Holmes County men—and then a man by the name of Peter Stuber threw a rock at Robinson.

The thrown stone started the uprising, and with that, it’s important to learn a little bit about the Knights of the Golden Circle. This was a group of Southern sympathizers who were active in Ohio and elsewhere, and they had an active chapter in Holmes County. These weren’t men who were necessarily for slavery or against abolition. Mostly, Knights of the Golden Circle simply wanted the Civil War to end, so they often featured prominently in draft uprisings.

And that’s what happened in Holmes County. Peter Stuber threw the stone that started this uprising, but he wasn’t among the Knights. However, the Knights did catch wind of what had happened, and they used the argument and the thrown stone to foment even deeper anti-draft sentiments.

After the altercation between Robinson and Stuber, tensions began to grow even further in Holmes County, and Captain James Drake, a Provost Marshal for the Union, rode to Robinson’s rescue. He arrested some of the men who had been involved in the argument, and Stuber, the stone thrower, later turned himself in.

You might think this would have been the end of it, but as Captain Drake marched his prisoners toward Glenmont, they were ambushed. The ambushing party was made up of angry locals and also a band of Copperheads, who were a sub-group of the Knights of the Golden Circle. About half a mile from Glenmont, they came upon Captain Drake’s party and staged a rescue of the prisoners. Drake, knowing he didn’t have enough men to hold his prisoners, was forced to let them go.

And tensions kept on growing from there. Once the prisoners had been rescued, men from all around Holmes County started gathering at a farmhouse owned by a man named Lorenzo Blanchard. Historical accounts say that they fortified the property, but stories differ as to how. Some claim that the group of rebels had artillery, though claims on this differ. One account says that the rebels had four artillery pieces, and another claims that they had only a rusty old cannon that someone had dragged quite far in order to bring it to the rebels’ defense.

Artillery or no, Blanchard’s fortified farmhouse would someday go on to be known as Fort Fizzle.

And in the meantime? Authorities learned about the newly forming rebellion in Holmes County, which led to the government sending Captain William Wallace, who was commander of the 15th Ohio Volunteer Army, to put an end to the rebellion. Captain Wallace brought 420 soldiers from Camp Chase in Columbus, partly via train though the men marched the last stretch of the trip through Holmes County.

They arrived at Fort Fizzle on June 17th—and found between 900 and 1,000 men arrayed against them. That sounds like it would have been a daunting sight to Captain Wallace and his 420 soldiers, but the soldiers were better prepared than the rebels. They fired a few shots at the rebels and their makeshift fort, and the rebels scattered.

That’s how it became known as “Fort Fizzle.” Everything shaped up like the rebellion would become a major battle—but after only a few shots, the rebels ran, and the “battle” fizzled out almost before it began.

The Aftermath of Fort Fizzle

While there were other, smaller protests around the Union, Fort Fizzle ended up being the largest Civil War uprising in Ohio. Ultimately, several men who took part in the Fort Fizzle incident were labeled insurgents and arrested. These men were taken to Cleveland, where they stood trial—but only one man, Lorenzo Blanchard, who was the owner of the farmhouse at which Fort Fizzle took place, was sentenced. He ended up serving six months of hard labor at the Ohio Penitentiary, after which President Lincoln pardoned him.

Another interesting thing about the Enrollment Act was that out of all counties in the state of Ohio, Holmes County had the highest number of draftees per capita with more than 2,000 men serving in the Union Army. Peter Stuber, the man who threw the stone that started it all, was among them, serving one year in the army before receiving an honorable discharge.

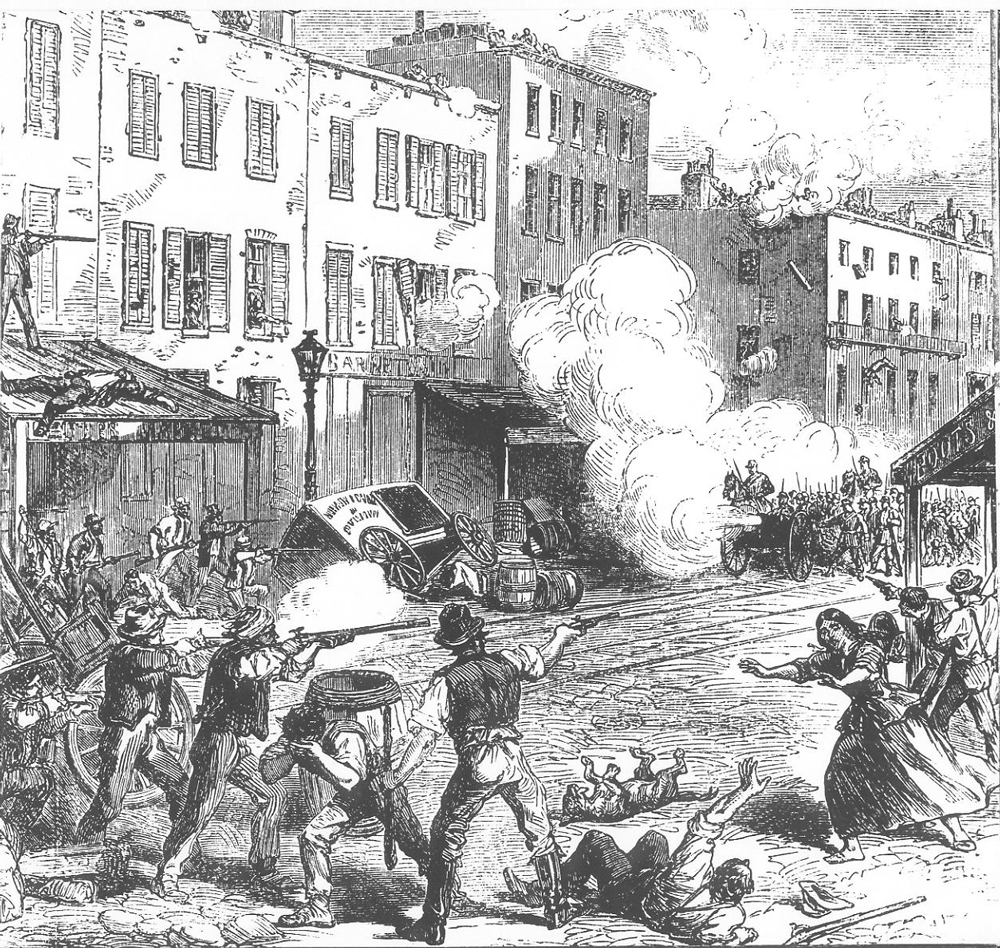

It’s hard to say whether Fort Fizzle played any part in inspiring what would become the largest of all the Union draft riots, but about a month later, in July 1863, rioting broke out in New York City. Thousands of workers began to attack government and military buildings.

Unlike Fort Fizzle, which fizzled out without much bloodshed—only two wounded—the New York Draft Riots took a major toll. By the end, African Americans had been targeted along with abolitionists and others. Published numbers say that 119 died in the riots, though there are some estimates that say the number could have been as high as 1,200 dead.

Fort Fizzle, or the Holmes County Draft Riots, is a little-known event in American history, one that is almost forgotten. But at the time, it loomed large on a national stage, an event that brought national attention to the small community of Glenmont nestled in the rolling hills of Holmes County.