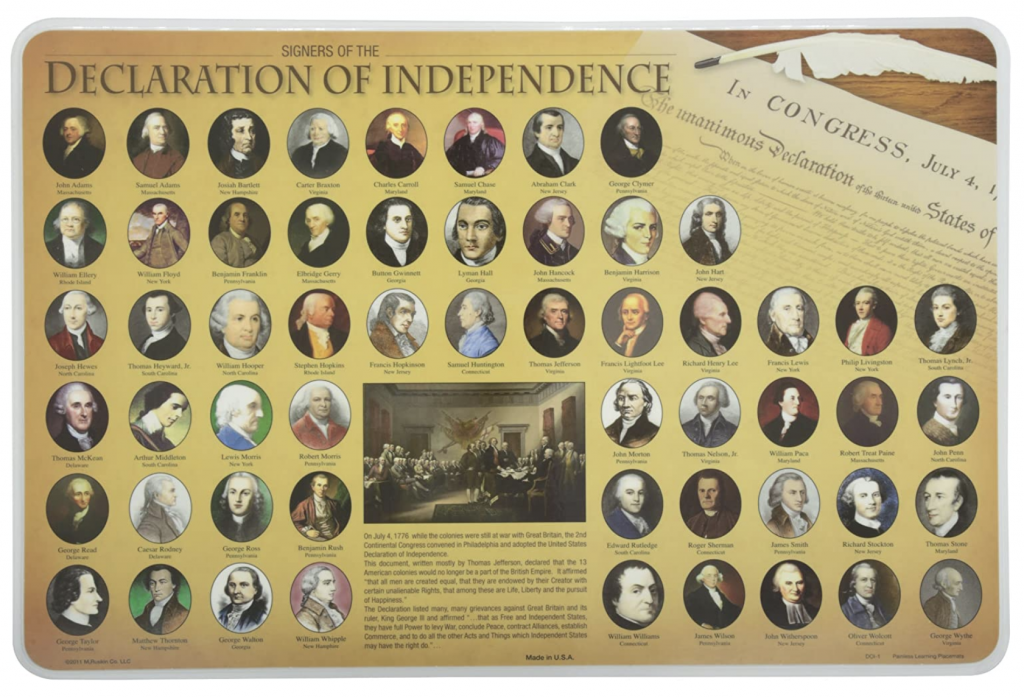

There were fifty-six men who signed the most famous founding document of our country–the Declaration of Independence. John Adams was one of them. In fact, going alphabetically, he was the first (though in actuality it was John Hancock who made the first, famously large and elaborate signature). Each signer had a unique and interesting background. Some are well known to history, even famous, while some are not. Each one who signed was a brave man, though, as they were putting their lives on the line by signing that document if the Americans did not win the Revolution.

Here are the stories of the men who signed the Declaration of Independence, beginning, in alphabetical order, with our second US President, John Adams.

John Adams was born on October 30, 1735, as the eldest child of John Adams, Sr. and Susanna Boylston. He was born in Braintree, Massachusetts. The site of his birth is now a historical park. His parents were both from Puritan backgrounds, so his upbringing involved religious education. His parents expected John, as their eldest son, to get a good formal education, which included grammar school and learning Latin. John did not like school, and often skipped it. He wanted to be a farmer, and he was one as a grown-up, dabbling to varying degrees in farming for his entire life, while having other careers, as well.

John wanted to drop out of school, but his father would not hear of it. In his later writings, John said his father told him, “You shall comply with my desires,” in regard to the dropping out of school issue. With that admonition, and with the hiring of a new teacher at his school who John liked, he stayed in school and eventually went to Harvard University when he was sixteen years old.

Once at Harvard, John did deviate from his father’s wishes by studying to be a lawyer rather than a minister. John most desired a career that would give him “honor of reputation” among his fellow students, as well as their deference, and he thought that studying law would best accomplish that aim.

John pursued a career in law upon graduation and eventually was regarded as one of the best lawyers in Boston. He had a thriving law practice while writing anonymous articles for the local newspaper that was critical of British acts in America, including the British-imposed Stamp Act. When the French and Indian War broke out, he was not expected to join it, as the soldiers were mostly from men from less well-off families than John’s. However, he struggled with the decision to remain a civilian, as he knew he was the first man in his direct male line in America to not belong to some militia or to fight in a skirmish or conflict.

John was heavily critical of British policies in America. His outspoken cousin, Samuel Adams, was better known in Revolutionary circles than John, at first. John eventually became to be as well known as Samuel, with a reputation as a man who believed in the cause of independence, but who would always do the right thing in any situation. This integrity is what led him to be the only lawyer in Boston who was willing to argue for the defense of the British soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre.

In the midst of all of this, his law practice, and his political activities, John managed to find time to court and marry Abigail Smith. Abigail was his third cousin, a daughter of the Reverend William Smith and his wife, Elizabeth Quincy. Together, Abigail and John had six children, four who lived past childhood, and two who outlived their parents. One of these children (one of the two to outlive John and Abigail) was their son, John Quincy Adams, who followed in his father’s political footsteps and became the sixth president of the United States.

As the 1770s wore on, John’s political activities became more prominent in his life than his lawyer career. The Coercive Acts and the Tea Act of 1772 were big points of contention between the colonists and Great Britain. John wrote strongly worded letters to Parliament about the unfairness and illegality of these acts. The letters got John on the radar of Parliament as a known political agitator. They kept an eye on him after that.

John was elected to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1775, representing the colony of Massachusetts. He maintained—at first—that to reconcile with Great Britain was the best choice. Later, he told Benjamin Franklin that he believed independence from Great Britain was inevitable. Later in 1775, John had become an outspoken proponent of independence from the mother country.

It was John Adams who suggested Thomas Jefferson be appointed to write the Declaration of Independence when the Continental Congress decided they needed one. Jefferson believed Adams should write it. John thought a Virginian like Jefferson would have an opinion with more clout among the British authorities, especially since the King and Parliament were not pleased with Massachusetts at the time, due to things like the Boston Tea Party and other acts of violence and defiance against British authorities in that colony. Duly, Jefferson wrote the Declaration, with Adams making some edits to his colleague’s first draft.

With the Declaration written and approved by the Continental Congress, the American Revolution was a go. Adams was incredibly busy during this time, serving on ninety war committees. He regularly worked eighteen-hour days during the war. In fact, he was so dedicated to the cause that other men in the Continental Congress referred to John as a “one-man war department.”

After the war, with America winning its independence, John became the first US ambassador to Great Britain. While serving in that capacity, several years later, he learned that his name was among only a handful of the most ardent revolutionary supporters who were not to be given a pardon by the Crown if Britain had won the war. His signature on the Declaration really was a move that put his life in danger, and he knew it when he did it.

After returning from Great Britain, he became Vice-President to George Washington, and then President after him. Truly, without the passion and commitment of John Adams to the independence cause, there may not have been a Declaration of Independence at all or even a Revolution. The free and independent America today is largely because of the heroic actions behind the scenes of John Adams.