The imperial nation of Japan launched an unprovoked attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii in December of 1941. Hawaii was not a U.S. state at the time, but was a territory of the United States, and under its governance and protection. The United States had been doing its best to stay out of WWII at the time, despite the attempts of the axis powers of Germany, Italy, and Japan to draw them into it. It was the Pearl Harbor incident that finally made the United States realize they had to enter the war.

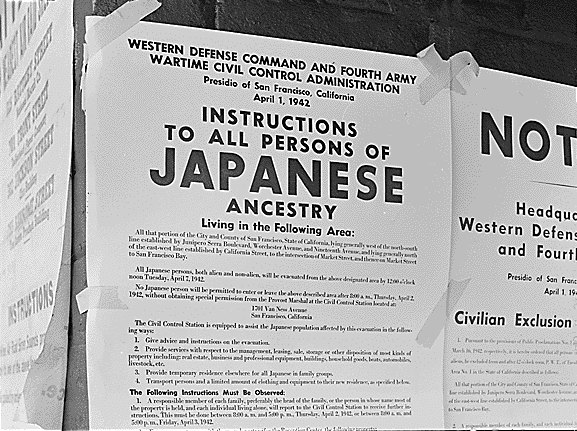

However, this proved to be unfortunate news for hundreds of thousands of Japanese Americans. There was already a suspicion, and in some areas, hostility, to those of recent Dutch and German descent in the United States, and internment camps were talked about for them, but never implemented. The Japanese and their descendants in America were not so lucky. Because Pearl Harbor was close to the west coast of the United States, suspicion toward Japanese Americans as possible Japanese spies was especially strong there. As a result of the Pearl Harbor incident, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February of 1942, just a couple of months after Pearl Harbor. This executive order forced the relocation of more than 117,000 people of Japanese ancestry into internment camps.

The people ordered into these camps were located on the west coast, and in places near it. Japanese Americans in California, Oregon, Washington, Arizona, Alaska, and Hawaii were ordered into the camps, and the camps were declared military areas. Approximately sixty-two percent of the people who had to go to the camps were U.S. citizens, most of them being second and third generation Japanese, who were born in the United States. There was a strong racist component to the order, as people who were as little as 1/16th Japanese, which meant they had one great-great grandparent who was Japanese, were sent to the camps, including infants and orphaned children who knew nothing of their Japanese heritage and could not possibly have posed any security risk to the United States.

The racism of the order can also be noted in who was ordered to go to the camps based on geography. Paranoia regarding Japanese people was high on the west coast, where more than 110,000 of the camp residents lived before going into the camps. In Hawaii, where more than 1/3 of the population was Japanese or of Japanese descent, the paranoia was not as high, because other island residents were used to them being there. Therefore, even though Pearl Harbor was in Hawaii, only about 1,800 Japanese there had to go to the camps.

Those affected by the order had to go to assembly centers near their houses, and from there were sent to one of ten permanent relocation centers. Most of those who went had to live in these centers for more than two years, until the executive order was revoked in December of 1944. A few lingered a bit longer, until all relocation centers were closed by 1946.

Ten War Relocation Centers were established in remote areas of the nation. (Courtesy of the National Park Service).

Roosevelt’s executive order also banned those of Japanese descent from California, and parts of Oregon, Washington, and Arizona, except for those living in internment camps there. Before the order went into effect in March of 1942, around 5,000 Americans of Japanese descent voluntarily left their homes and moved to other states that were outside of the so-called “exclusion zone.” These people did not have to go to the camps, because they left the west coast of their own accord before the order went into effect. Those who did not leave, usually because they owned homes and/or businesses or had family there, went to the camps, rather than risk losing everything they worked so hard to build. They hoped it would all still be there for them when they were released, as they hoped they would be.

While these were not the death and forced labor camps the Jewish people and other targeted groups were sent to in Nazi Germany, conditions in the camps were far from favorable. The military was obligated to provide the residents with the minimal standards of housing, clothing, and food that they would give to the lowest ranking member of the military. Schools were set up for children, and some sports were engaged in for recreation by the adults, but it was, by and large, a brutal, hardscrabble existence. The camps were nominally meant to be temporary, until living arrangements could be found for the detainees outside of the exclusion zone. Most ended up staying until the executive order was rescinded. A few were shot for walking to close to the fence borders of these camps. About 4,000 college students did receive admission to colleges in the east, outside the exclusion zone, and were able to leave the camps to continue their educations.

In 1980, the Japanese American Citizens League pressed President Jimmy Carter to open an investigation into whether the internment camps were justified. His appointed Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians found no real evidence to justify putting Japanese Americans in these camps, and concluded the camps were based on racism. The commission recommended reparations be paid to survivors of the camps. President Ronald Reagan formally apologized for the camps in 1988, and authorized paying $20,000 to each survivor of a camp. The U.S. government eventually paid approximately $1.6 billion in reparations to 82,219 Japanese American camp survivors and their heirs.

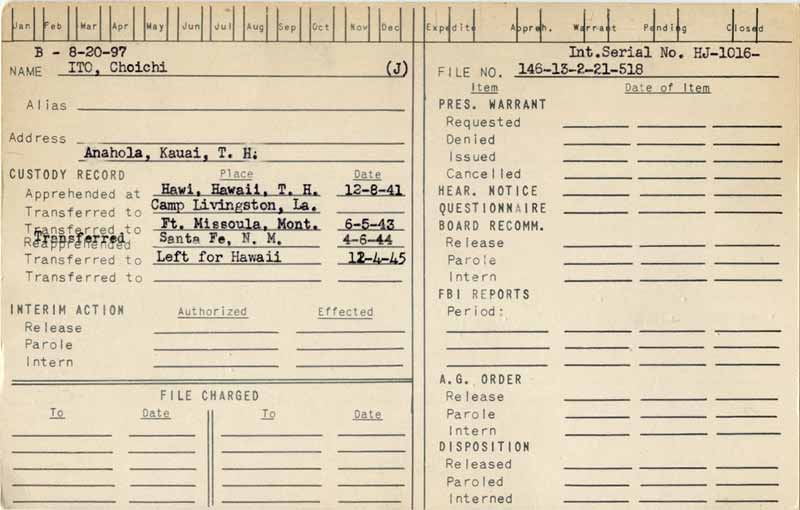

Index Card for an individual in the WWII Alien Enemy Detention and Internment Case Files, (Record Group 60).

If you have ancestors who were in the Japanese internment camps and want to research them further, learn more about their experiences in the camps, and what happened to them after they left the camps, the National Archives has a strong collection of these records. Some of the ones you will want to explore include:

War Relocation Authority Records:

These are in Record Group 210 and contain personal and descriptive information on each individual person who was placed in a Japanese American internment camp. The records are also searchable online from the website of the National Archives.

WWII Alien Enemy Detention and Internment Case Files:

Record Group 60, these records document administrative proceedings in which aliens who were considered enemies to the United States were released, released on parole, or interned.

Compression and Redress Case Files:

Record Group 60, these are records of approximately 26,550 claims for compensation from those who were removed from the exclusion zone and/or put in camps. They are asking to be compensated for losses of real estate and personal property. The claims date back to 1948.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians:

Record Group 60, these are President Carter’s commission findings, which include testimonies from more than 750 witnesses to what went on in the camps.

Office of the Provost Marshal General:

Record Group 389, these records include information about the release of individuals from internment camps, as well as Japanese American men who were deemed eligible for military service during WWII. Personal data cards and more are included in this collection.

Record Group 499, these records are from the assembly centers people went to before being sent to the camps, and include folders of information on individual families. This is an excellent personal genealogical resource for those looking for more than just dates and names.